The Grave of John Alfred Groom in Highgate Cemetery (Image © A Grave Announcement).

Whilst wandering the main footpath in Highgate East, I almost passed this monument without comment, preoccupied with the vista of the armies of grave markers saluting the woods. It was an unassuming example of the popular scroll headstone, somewhat discoloured, its text fading like an ageing memory. A pockmarked wreath rested atop its surface, contemplating the disappearing tendrils of ivy interspersed with the text. I moved closer and noted the epitaphic biography lining the stone:

IN

IN EVER ABIDING MEMORY

-OF-

JOHN ALFRED GROOM

DIED 27TH DECEMBER 1919

FOUNDER OF

THE CRIPPLEAGE,

CLERKENWELL, LONDON

AND THE ORPHANAGE

CLACTON-ON-SEA

A SERVANT OF GOD

AND A FRIEND OF THE POOR,

THE ORPHANED AND THE AFFLICTED.

The words moved me to action. I was determined to look into his life. The terminology both appalled and intrigued – what was this so-called ‘Crippleage?’ What kind of work was done there? The phrase seemed to conjure up a series of Dickensian horrors in the form of a crude workfare narrative, the grimness of a quid pro quo penury. At the same time, the notation of ‘the poor, the orphaned and the afflicted’ felt like a clarion call to altruistic acts. I felt as if I had to explore, as others have done, the figure of John Alfred Groom, metaphorically cleansing the dirt and grime from his stone, restoring his memory to an unblemished condition, unearthing, uncovering and, ultimately, revivifying. In doing so, I could perhaps in turn learn a little more about the vulnerable individuals he made it his mission to assist.

John Alfred Groom was born at 6 North Street, Clerkenwell, London on the 15th of August, 1845. He was the third son of Sarah Maria Groom and her husband George, a copperplate printer. Sarah Wigton had married the latter on the 21st of September, 1840 in St. Pancras, an area of London adjacent to where the family would settle. At first, Sarah and George lodged at Brunswick Place in a house with seven other individuals: two families, the Welfords and the Fieldings, in addition to fifteen-year-old labourer John Trott. Conditions must have been rather overcrowded, and it is no surprise to discover the Grooms residing elsewhere by 1851, now occupying 6 Field Terrace following their move from John’s birthplace.

After leaving school, John started work aged fifteen as an errand boy (termed ‘lad’ on the census) for the Inland Revenue. The appointment was not to last for long. He soon undertook an apprenticeship in engine-turning, during which training he became highly skilled in the art of silver-engraving. Indeed, at the age of 21, he set up his own business in the latter, running proceedings from a glass-fronted shed in the garden of the family home.

An example of a ‘situations vacant’ advert for engine turners, printed in the Sheffield Daily Telegraph on the 21st of December, 1865. © British Newspaper Archive

Amidst all this activity, tragedy struck. In 1866, George passed away at the age of 46, leaving Sarah to raise six children alone. She must have been an indefatigable woman. The family took solace from the loss in their beloved church, where John had been a Sunday school teacher since the age of 16. John himself, as the eldest child remaining at home, was also forced to adopt more of a parental role, assisting his mother in tending to his siblings. The experience likely served him in good stead for his later pastoral efforts helping the vulnerable, informing his need to minister to those whom society had all but forgotten. Indeed, he was already developing a social conscience. In company with a friend who had been appointed a City of London Commissioner, John spent a considerable amount of time in the so-called slums, witnessing at first hand the abject poverty and despair written on the faces of the inhabitants. Their quiet and determined suffering struck an insistent chord within him. John felt a growing determination to help.

‘Bluegate Fields,’ a slum area in the east end of London, illustrated by Gustave Doré in 1872.

Not long after his business had been established, John was asked to lead a mission hall in the neighbourhood as voluntary superintendent. Whilst his brothers kept his affairs in order, he was able to devote himself to philanthropic endeavour, expending increasing amounts of time and energy upon his new charges. At the same time, travelling much through Farringdon Market had brought him into contact with the situation of the blind and disabled girls who thronged the nearby streets, hawking flowers and watercress to passers-by. These individuals made a precarious living, seasonal and often beset by the vagaries of the weather, sleeping outdoors and, on market-days, ready for action by four o’clock in the morning. The London City Press on the 19th of August, 1871, emphatically details their lot, terming such vendors ‘a forlorn, broken-down set, with scarcely a ray of hope in this world, and next to none in the other.’ They have, in the newspaper’s words, ‘fallen down the ladder of life.’ Their plight was such that John was galvanised into action.

London Life. Flower-Sellers. © New York Public Library

In 1866, having hired a local meeting hall on Harp Alley near Covent Garden, John founded that which is inscribed upon his grave: ‘John Groom’s Crippleage,’ also known as the ‘Watercress and Flower Girls’ Christian Mission.’ Here, the flower-sellers were able to obtain a cup of fortifying hot cocoa in the mornings and, for a small contribution, a warm meal twice-weekly. The organisation became a centre, a hub for vulnerable individuals whose lives were characterised by insecurity, desperately trying to make ends meet. The girls were encouraged to attend to their ablutions, practising a good level of personal hygiene and self-care. Simultaneously, John, who termed himself a ‘voluntary evangelist,’ would read them Bible stories, hoping to inculcate within them a moral framework to guide their future activities, whilst also urging participants to attend one of three Sunday schools established in the area. Whilst this sounds to our ears like rather too many strings attached, it was considered progressive at the time, a small beacon of hope for those condemned to wander the streets in search of a living.

John’s efforts did not go unrecognised. The Earl of Shaftesbury publicly announced his support of the venture, becoming the organisation’s president, a development which was said to have ‘contributed greatly to its welfare’ by the Islington Gazette (11th July, 1873). He also brought in much-needed funds, taking advantage of his many contacts. Indeed, Shaftesbury had noticed John, a distinctive figure commonly found berobed in a top hat, whilst himself visiting the more impoverished sectors of the city as part of his political work seeking reforms for the working poor. The two became fast friends, often to be seen together, the aristocrat and the preacher, an unlikely duo.

Portrait of Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury by John Collier © National Portrait Gallery, London

Shortly after the project’s inception, wedding bells rang out. Sarah Farmington, the daughter of a coachman, married John on the 5th of March, 1868. Groom was now a groom! The couple went on to have four children, three sons and a daughter, as noted below in this copy of the 1881 census, moving into 8 Sekforde Street in Clerkenwell, a terraced house to which a blue plaque commemorating John’s legacy is now affixed. Sarah was an invaluable support to her husband, assisting with his enterprise and proving herself to be an industrious worker. Her contribution to the work of the mission should not be underestimated – she threw herself into proceedings with a relentless energy.

1881 census depicting John Alfred and Sarah Groom with their children © Findmypast

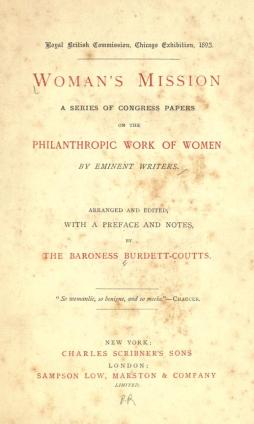

Now a married man, John persevered with his project, devoting himself to supporting his clients. Professionally, however, he was dissatisfied. Despite operating a centre available for those needing assistance, he soon found that his wish to provide blind and disabled girls with the means to become self-sufficient remained unfulfilled. Whilst a number of attendees were able to secure a position in domestic service, the majority continued to eke out a meagre living on the streets. John wanted to ensure that his charges became more independent and, like all good stories, the solution to the conundrum lay with a woman now almost written out of this particular tale – the Victorian philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts.

Angela Burdett-Coutts, Baroness Burdett-Coutts (1814-1906) by Francis Henry Hart © National Portrait Gallery, London

Angela was extraordinarily wealthy. In 1837, she was suddenly catapulted into the limelight as one of the richest people in the country, having inherited her grandfather’s estate, a fortune worth in the region of £1.8 million, equivalent to a staggering £108,750,000 in 2019. Angela chose to use this money for charitable purposes, establishing scholarships, making endowments and financing philanthropic ventures. She was particularly interested in the plight of the poor and, as a result, had become aware of the hardship and adversity facing the disabled London flower-sellers. In 1879, she had founded a ‘Flower Girls’ Brigade’ designed for those between the ages of 13 and 15. This was supplemented with a factory in Clerkenwell, installed for the purpose of instruction in the art of artificial flower-making. Her primary focus was the security of the girls – she made sure that they received police protection and were protected from the dangers of exploitation. A charitable industry thus rose up, providing clients with the opportunity to teach themselves a skill, establishing a ready-made community into which those formerly condemned to the streets, both with and without disabilities, could enter and, it was to be hoped, flourish.

At this point, John enters the picture. Angela, having become acquainted with the work of his ‘Watercress and Flower Girls’ Christian Mission’ and recognising his desire to furnish the clients of his organisation with a more sustainable means of support, prevailed upon John to devote himself to the enterprise of artificial flower manufacture. He agreed to her request, provided that the following condition be met: that Angela finance the hiring of a manager to oversee John’s engraving business. This arrangement once made persisted until Angela’s marriage in 1881, an affair which scandalised Victorian society as the 67-year-old heiress wed 29-year-old American William Lehman Ashmead Bartlett. Having thus married an alien, she was forced to forfeit her inheritance, retaining precious little capital for her causes. This new paucity of funds compelled the so-called ‘Queen of the Poor ‘ to step back from her life’s work, focusing instead on her husband’s political career at Westminster.

Angela does not receive due credit for her involvement in the formation of John’s enterprise – in many pieces researching the history of the flower-making girls, she is simply omitted, an irrelevance in an otherwise grand tale of patriarchal redemption. Whilst reflecting upon the story of John Alfred Groom, therefore, it is imperative that we remember Angela’s key role in the decision to diversify John’s association, and that, without her persuasive efforts, he may well not have embarked upon this industry. In writing this piece, then, I also hope to honour Angela’s memory and give credit where credit is very much due.

Following John’s assent, Angela withdrew from the quotidian administration of her Flower Girls’ Brigade. This, in turn, became the industrial sector of the business, the profits of which paid John a salary. The Mission Hall became a de facto factory with all rushing to offer assistance. Indeed, it was a true family affair – John’s brothers supplied the machines. A cousin, Jane Holiday, is even listed on the 1891 census as ‘Artificial Florist Forewoman,’ a memorable title.

1891 census detailing the role of John’s cousin Jane: Artificial Florist Forewoman. © Findmypast

In order to offset the seasonal precarity of the occupation, a programme was devised whereby, during the summer months, bouquets of genuine flowers were made up and offered for sale on the premises, and, during the winter time, artificial blooms were crafted, spots of colour to counteract the drabness and dinginess of the London winter chill. The latter flowers themselves were made from the fabric ‘sateen.’ From this material, fed into the machines, petals were cut to size. Once these had been obtained, the girls would colour the pieces, attaching them to a wire stem bedecked in green paper. This was a task requiring extraordinary skill: a deftness characterised by precision, care and speed. Many of the girls became highly adept at producing even the most intricate of flowers in an impressive trompe l’oeil. In 1888, the fruits of their labour were displayed at the ‘Women’s Art Exhibition’ held at the Royal Concert Hall for the purposes of demonstrating ‘what women can do.’ The Hastings and St. Leonard’s Observer on the 1st of December details the magnificent results of the artificial flower-makers, asserting that their presentation was ‘one of the most effective exhibits in the whole room.’ The newspaper contended that ‘a nearer approach to reality could not be conceived; one feels almost inclined to seize a bouquet and expect to scent a pleasing aroma from them.’ This was the affirmation that the organisation needed – John and his team renewed their efforts, driven by a now reinforced sense of purpose.

In 1894, the expanding company moved to larger premises at Woodbridge Chapel, in the environs of Sekforde Street. The sheer scale of the enterprise meant that the volume was now such that the product could be sold wholesale to businesses and private residences. John remained an ardent campaigner on behalf of the association, generating an influx of donations which enabled the charity to further refine its provision. Indeed, such monies enabled the lease of a number of dwellings near the factory where clients could be housed, overseen by a series of newly-employed ‘house-mothers.’ Such monetary gifts were made to stretch even further – in 1890, John opened a ‘Flower Village Orphanage’ at Clacton-on-Sea.

John Groom’s Orphanage in Clacton-on-Sea © Colchester Gazette

This institution doubled as both a home for those children whose parents had died or subjected them to abandonment, and a holiday resort not only for the London flower-makers, but also, at certain times of the year, disabled children from the city. In a letter to the Kent & Sussex Courier on the 12th of May, 1899, John urges readers to donate to the retreat’s summer programme, designed as a period of respite for those ‘sightless and helpless little ones’ who found themselves part of the ‘vast army of slum children sent away every year to the various holiday-homes.’ The Groom retreat, he claims in his missive, is specially fitted out for such children, and brings a ‘ray of sunshine’ into their ‘dreary lives,’ the chance to leave behind the smog of the city for the untamed azure of the sea. Ten shilling contributions are sought, a sum sizeable enough to fund a fortnight’s stay for one of these unfortunate souls. The offering was a roaring success. Not long afterwards, five other such homes were opened, all of which were, appropriately, named in honour of a flower, housing around one hundred disabled girls between the ages of two and twelve. The children were raised to go on to things which many thought impossible for the ‘afflicted’ – an education, employment in service, and, of course, London flower-making. Even after they had departed, John urged his former charges to keep in touch, offering them ongoing ‘counsel and advice’ (Heywood Advertiser, 29th of March, 1912).

John Alfred Groom’s letter to the editor seeking donations, published in the Kent & Sussex Times on the 12th of May, 1899. © British Newspaper Archive

Amidst such noble exertions, the flower-girls continued to make an impression, going from strength to strength at the site of the new factory. In addition to their commercial undertakings, they took part in many exhibitions, advertising the product to new audiences, demonstrating their dexterity and serving as a living example of Groom’s philanthropic designs. In 1905, for instance, an exhibition of artificial flowers crafted by those from ‘Mr J. A. Groom’s Industrial Training Homes for Crippled and Afflicted Girls’ took place in Oxford Town Hall. The blooms were the subject of lofty praise in the Oxford Times on the 27th of May of that year, being ‘an exceedingly close copy of Nature’ and remarkably versatile, suitable for ‘conservatories, dining-table and drawing-room decorations, as buttonholes, and for evening dresses.’ The girls were able to prove, to a contemporary society often morally selective in its treatment of the needy, that to have a disability was not to be without ability, and that remarkable hardship could be overcome. It was claimed that the enterprise offered a chance to those for whom life had a ‘blank outlook’ and was scarcely ‘worth living,’ teaching ‘poor helpless girls how to help themselves.’

At any one time, there were around 150 disabled workers engaged in John’s flower-making industry, drawn from across the United Kingdom, instructed in the art and given the tools to make a living, earning around fifteen shillings a week. Queen Victoria herself was said to have taken a ‘loving, keen interest in their work,’ and to have sent intermittent funds to the cause. Queen Alexandra and the Princess of Wales also maintained this royal focus, often requesting samples for review. Clearly, then, the disabled girls and their situation made a resounding impact throughout society, providing the wealthy and the elite with an easy outlet, albeit rather paternalistic, to contribute to the alleviation of the sufferings of poor unfortunates and to assuage their own guilt. It is important that we do not forget, however, that for every John Alfred Groom and for every flower-girl, there were those without such opportunity, those who withered like a dying bloom on the streets, those cast out from their families, objects to be pitied, feared, scorned, and, ultimately, spurned. Even amongst John’s operation, assistance came at a price – there were rules to be followed and regulations to be upheld. It was not a disinterested help that aided the disabled and the so-called ‘afflicted,’ but one informed by an entrenched model of the privilege ingrained within narratives of Christian salvation.

A preserved example of the artificial flowers crafted by John’s organisation. © Colchester Gazette alike.

In 1906, business was booming, the reputation of John’s work ever-growing. Indeed, the flower-makers were honoured by being chosen to decorate the London Guildhall for the Lord Mayor’s banquet, the results of which received great praise. In that same year, however, a personal tragedy befell John – his wife, Sarah, passed away. She had been his great support, providing constant aid and advice. She had also brought up three sons and a daughter. Her loss must have been devastating. Yet John could not afford to waver. He threw himself into his work, taking solace in offering help to others. Two years later, he found happiness again, marrying Ada Wood, a hospital nurse, the daughter of a contractor. In 1911, the newly-weds were living at John’s accustomed 8 Sekforde Street, with all four of his children, a nephew, and two of his charges as boarders. The engine-turning company, established long ago by John prior to his philanthropic projects, continued to be run from the address, now by his sons, Alfred and Herbert. John was a memorable fellow, a character always to be found berobed in a top hat. Such headgear would only removed when in attendance at a football, swiftly exchanged for flat cap. He was an avid supporter of Chelsea Football Club and was frequently seen at home games. Nobody forgot John. He was a fixture in the neighbourhood, known to rich and poor alike.

1911 census depicting the busy household of John and Ada Groom. © Findmypast

Queen Alexandra’s support, as noted above, continued to flourish. In 1912, she placed an order for thousands of hand-crafted roses which were to be sold on the inaugural ‘Queen Alexandra Rose Day,’ held on the 26th of June, the anniversary of her move to Britain. The event raised approximately £18,000 for charity (c. £1,061,000). Whilst in her native Denmark, the queen had witnessed the efforts of a priest selling such blooms to support those in need. She resolved to transport the idea overseas. Indeed, even today, ‘Alexandra Rose Day’ is celebrated. This was far from the only royal order presented to the flower-makers. A previous request had seen the girls produce £30,000 flowers to be produced for a banquet in honour of the king and queen of Norway. The renown of ‘John Groom’s Crippleage and Flower Girls’ Mission,’ was clearly such that its manufacturers’ skills were recognised both nationally and internationally. John’s early designs had finally come into bloom – this was a self-sustainable enterprise, providing food and shelter for those with disabilities, sponsoring those whom society had disregarded.

Alexandra Rose Day sellers assist the Preston Mayoress [sic] (Lancashire Evening Post, 15th of June, 1935). © British Newspaper Archive

It surprises many who look into the life and times of the flower-girls that their craft was responsible for the emergence of some of the first poppies as reverential symbols of lives lost in combat. In 1916, John’s association was approached by a group of women in Whitby who asked them to assemble a batch of poppies to be sold. An impromptu ‘Poppy Day’ was born, an occasion on which a donation would secure one a flower, the profits of which would, in turn, aid injured soldiers. The practice proved enormously popular and soon became an annual event adopted by the Royal British Legion. It is clear, therefore, that the industry for which the flower-girls laboured had a considerable impact on the socio-cultural fabric of the nation, involved in cementing several traditions in which we still partake today.

In 1918, however, tragedy struck as John passed away. His increasingly failing health had brought an end to his charitable work as superintendent and secretary of the mission in which he was a self-styled ‘baptist minister.’ Throughout the final year of his life, he occupied a room in the Clacton Orphanage, living amidst the realisation of his aspirations, witnessing the prospering of his charges. Shortly after Christmas, on the 27th of December, 1919, John passed away. He was interred on the east side of Highgate Cemetery.

John Alfred Groom and his son Alfred. © National Portrait Gallery

Following his death, Alfred, John’s eldest son, took over management of the organisation, leaving the Groom’s engine-turning business to his younger brothers. The flower-selling industry continued to prosper under his leadership, expanding to such an extent that manufacture was transferred to a larger site at Edgeware. Here, a de facto village rose up, with houses constructed to accommodate the workers arranged in such a way so as to encircle the newly built factory. 300 disabled girls lived and worked in this place, processing an enormous volume of flowers every year. Indeed, in 1932, around 14 million of the so-called Alexandra Roses were produced on this site.

An April 1944 Advertisement for ‘John Groom’s Crippleage.’ © Grace’s Guide

Like all great empires, rise gave way to fall. The business of flower-making did not fare well in the first half of the twentieth century. The instability that had once driven John to offer help to those selling fresh blooms on the streets of London returned with a vengeance to afflict their artificial counterparts. As demand shrank, the organisation was forced to remodel itself, eventually even admitting boys in 1965. Whilst maintaining an interest in fostering independence amongst attendees, focus was now very much on the housing of the disabled alone. No longer were those admitted engaged in the labour of flower-making. Furthermore, with Victorian attitudes to disability disappearing in the rear-view mirror, more emphasis was placed upon accommodating those considered to be unlikely to obtain or keep gainful employment, a new state of affairs brought to bear by a growing reluctance to seek the moral edification and practical training of those deemed burdensome to society. In the aftermath of the two world wars and the improved awareness of the disabled generated by the return of so many wounded veterans, the grand old moral strictures of Christian programmes of salvation began to fall out of favour. Indeed, John’s former mission was renamed ‘John Groom’s Association for the Disabled,’ a new name for a new start.

In 1979, the organisation ceased its work with children. It was the end of an era, the culmination of over a century of furnished aid for those considered impoverished and needy. Activities regarding the housing of the disabled were expanded – ‘John Groom’s Housing Association’ became an official registered charity. Flats and complexes were constructed throughout the country. John Groom’s Court, for instance, occupies a site in Norwich and is still in operation for those with ‘physical and intellectual disabilities.’ A subsidiary, ‘Grooms Holidays,’ worked to arrange vacations for the disabled in the UK. Such independence was not to last for long. In 2007, two old friends met once again when the charities John Grooms and the Shaftesbury Society were merged, adopting a new Christian identity under the name of ‘Livability.’ The original aims of John’s association now live on as the inspiration for a range of community engagement projects and services for disabled people. The work continues.

The logo of Livability, a charity created from the merger of John Groom’s mission and the Shaftesbury Society.

In telling this story, I have attempted to give life to John, Angela and the flower-making project. Finding the voices of the girls themselves, however, has proved to be much more difficult. It is therefore incumbent upon us that we do not allow the forces of an easy nostalgia to dictate remembrance of the services described here. Whilst John’s aims were undoubtedly admirable, a capitalistic model of services rendered propped up the foundations of this charitable entity. An emphatically patriarchal framework imposing aid through the paternal lens of the Christian mission, a status quo where physical redemption was dependent upon the surrender of your mortal soul to a clearly circumscribed moral schematic, was at the heart of the establishment.

Endemic societal attitudes to disability also meant that all was not rosy (pun intended). To our ears, the terminology adopted by John and his mission, reinforced by the echo chamber of his contemporaries, is starkly discriminatory. To read of the establishment of such an organisation as the ‘Crippleage’ is a confronting experience – violating and dehumanising. Former residents substantiate this entrenched prejudice, speaking of their status as constructed spectacles for the so-called able-bodied, their disabilities fetishised, performative mirrors used to confirm innate biases. Even the designation ‘flower-girl’ was one of tacit disparagement, conveying, as Huneault notes, a ‘belittling immaturity’ in accordance with the ‘infantilizing requirements of a patriarchal culture.’ We must always keep in mind that such philanthropic labour is visible to us through the distorted lens of those who were themselves responsible for the very charity itself.

We have come a long way from the days of ‘helping the helpless to help themselves.’ Yet we still have a long way to go. Now more than ever, disability rights must be protected. We must safeguard what has been hard-fought. We must keep fighting to construct a society where there is opportunity for all. Let’s keep on integrating, not segregating, until John’s mission is a thing only of the past.

Blue plaque situated at the former residence of John Alfred Groom, 8 Sekforde Street, Clerkenwell © London Remembers

💀 Thanks for Reading!

A Grave Announcement (@AGraveAnnounce)

Bibliography

The following general web resources proved very useful in the completion of this research:

The following websites provided valuable background information on John and his family, the Earl of Shaftesbury and Baroness Angela Burdett-Coutts:

P. Higginbotham, ‘John Groom’s Crippleage and Flower Girls’ Mission, Clerkenwell, London (Children’s Homes). http://www.childrenshomes.org.uk/ClerkenwellGroom/ [accessed 10 June 2019].

K. Huneault, ‘Flower-Girls and Fictions: Selling on the Streets’, RACAR revue d’art canadienne / Canadian Art Review 23, no.1/2 (1996), 52-70.

L. Oldershaw, ‘Clacton’s Historic Flower Girls and their Royal Connection’, in the Colchester Gazette. https://www.gazette-news.co.uk/news/15463243.clactons-historic-flower-girls-and-their-royal-connection/ [accessed 29 June 2019].

L. Oldershaw, ‘When Barnado’s was the Crippleage and Flower Girls’ Mission and floral fundraisers put Clacton on the map in the 1900’s’, in the Colchester Gazette. https://www.gazette-news.co.uk/news/15469022.when-barnados-was-the-crippleage-and-flower-girls-mission-and-floral-fundraisers-put-clacton-on-the-map-in-the-1900s/ [accessed 29 June 2019].

M. Pottle, Groom, John Alfred‘, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography [accessed 10 June 2019].

J. Simkin, ‘Angela Burdett-Coutts,’ (Spartacus Educational). https://spartacus-educational.com/EDburdett.htm [accessed 2 July 2019].

‘Sekforde Street area’, in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), pp. 72-85. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp72-85 [accessed 10 June 2019].