‘the Lancashire Girl who was called to nurse a King’

Todmorden Advertiser and Hebden Bridge Newsletter, May 1st 1903

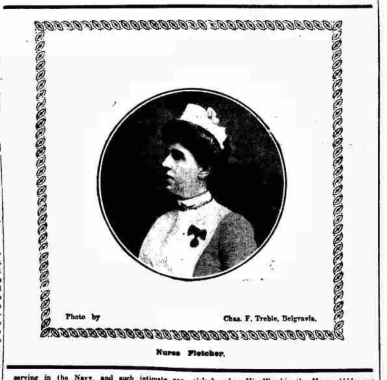

Nurse Annie Fletcher (Wigan Observer and District Advertiser May 14th, 1910)

I have previously written about my meanderings in All Saints Churchyard in Marple, Stockport, and the burial ground’s viridescent grave settings, interspersed with pathways of charmingly disordered stones, recycled and reused to form these sepulchral avenues. I had discussed my encounter in this place with Lieutenant Edmund Turner Young and his family memorial, a man lost on the sandy shores of Gallipoli at the age of 33. My eye was also struck, however, by a grave marker in black marble, seeming to sparkle iridescently in the dappled light of a sporadic sun.

The grave of Annie Fletcher (and sister Mary). Image by A Grave Announcement

The inscription was addressed to one Annie Fletcher (Nan), advertising her profession as that of Resident Nurse to their Majesties King Edward VII, Queen Alexandra and Princess Victoria. I wondered why a testament to such esteemed royal service was situated in a rural parish churchyard, unassumingly guarding the adjacent cobbled pathway, mingling with the other stones of churchgoers long gone. The lengthy epitaph reads as follows:

Sacred to the Memory of

Annie Fletcher (Nan)

of

“Vedal” Heeley Road, St Annes-On-Sea.

Died 13th May 1933, Aged 68 Years.

For 30 Years Resident Nurse

(Betty)

To Their Majesties

King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra

and

H.R.H. Princess Victoria.

Also Mary Horton

Sister of the Above

Died 22nd December 1960

In her 90th Year

“At Rest.”

Ann Fletcher (known to all as Annie) was born in 1865 in Beeston, Yorkshire, the first child of William and Sarah Fletcher, whose origins lay in Aspull, Lancashire, a town near Wigan. Her father was involved in the coal-mining industry from an early age – on the 1851 census he is listed as a waggoner from the age of eleven. This was a back-breaking job necessitating the pushing of heavy and loaded carts away from the coalface. By 1871, Sarah and William had moved to Wigan where they were living at Ormandys Houses, a row of terraces south of the town centre, adjacent to the Leeds and Liverpool canal . Here, the six-year old Annie was joined by a brother, three-year old John William Fletcher, and a sister, new-born baby Mary, as seen on Annie’s grave marker above.

Beeston, West Yorkshire, Birthplace of Annie Fletcher (‘Beeston. West Yorks. Station 1779989 ae7d591c’ by Ben Brooksbank is licensed under CC BY 2.0)

The personal drive and ambition of Annie’s father ensured that the family rose through the ranks. Following another move to the town of Buckley in Flintshire, North-East Wales, William obtained the position of Colliery Manager, rising impressively from the lowest rung of the ladder to a senior managerial position in a 29-year period. There were now seven children, ranging from the ages of one to sixteen.

A Typical Coal-Mining Scene (‘Coal-mining’ by The Graphic 1871 is licensed under CC BY 2.0)

Annie, however, had been working as a nurse since 1891, associated with the Women’s Hospital in Shaw-Street, Liverpool, a place she had entered in 1889, during which time she trained under Miss Carless. From August 1893, to March 1896, she was made charge nurse. It was at this time that she encountered Royal Surgeon Sir Frederick Treves (1853-1923), the man responsible for the care of Joseph Merrick, the so-called “Elephant Man.” Having repaired for a while to Manchester, she undertook a brief stint in a similar hospital for women. In 1901, she went down to London where she held a series of other nursing appointments, one of which was as matron of a small hospital, before joining the staff of Miss Ethel M’Caul’s (1867-1931) nursing home. The latter was a Royal Red Cross nurse and prominent figure in the London nursing community who had established this private medical institution at 51 Welbeck Street. It was fitted with fifteen beds, an operating theatre and a staff of twenty, of whom ten were nurses.

Sir Frederick Treves (‘Sir Frederick Treves. Lithograph, 1884’ by the Wellcome Trust licensed under CC BY 2.0)

This experience held her in such good stead that she became affiliated with the King Edward Hospital in Grosvenor Gardens and the Royal Physicians who operated there. The meteoric rise of her career was outlined by the Wigan Observer and District Advertiser of the 14th May 1910 as follows:

‘At first she was associated for several years with the Hospital for Women in Shaw-street, Liverpool, and before joining the staff of the nursing home under Miss Ethel M’Caul, R.R.C., she held other nursing appointments, among these being that of matron of a small hospital. She had so perfected her training in the profession she adopted that she was able to become associated with the King Edward Hospital, Grosvenor Gardens, London, with which the Royal physicians were identified, and in this way she became the King’s nurse.’

As a consequence of this, she took on the role of Second Nurse to King Edward VII himself in 1902, following his operation for appendicitis which had caused the coronation, set for the 26th of June 1902, to be postponed. Annie had taken on responsibility for the night shift in the rota, relieving her colleague Miss Haine. Both nurses had been selected on account of their special knowledge of abdominal surgery. The procedure itself, performed by Sir Frederick Treves with a Miss Tarr as surgical nurse, at that same private nursing home of Miss Ethel M’Caul, had been somewhat revolutionary – a small incision was made in the abdominal wall, through which a pint of pus from the infected abscess was drawn. Edward made a swift recovery, apparently even sitting up in bed the next day smoking a cigar. The very same operating table upon which the King had lain was later marked with a metal plate with the King’s signature commemorating the event. Edward, however, had reportedly been a rather difficult patient, but ‘met his match in Sister Fletcher,’ according to the latter’s obituary in the Aberdeen Press and Journal of the 19th of May, 1933:

GAVE KING AN ORDER.

‘There has just died perhaps the only commoner in the realm who ever gave an order to King Edward and insisted on it being carried out…This was Sister Annie Fletcher, who nursed him through the appendicitis that caused the postponement of his coronation.

King Edward was not the most amenable of patients, but when it came to taking (or rather, to his thinking of not taking) his medicine, he met his match in Sister Fletcher.’

Her conduct during this difficult period of ill-health for the king resulted in her permanent appointment to the nursing staff of the Royal Household, caring not only for Edward but also for his wife Queen Alexandra and daughter Princess Victoria. Annie had been personally thanked by the King and presented with, in the words of the Wigan Observer and District Advertiser (25th November, 1905), ‘a valuable gift.’ She accompanied the family on their European travels and even stayed on the Royal Yacht, the “Victoria and Albert,” for summer cruises. It was on the latter that King Edward recuperated once he was well enough to leave hospital after his surgery.

The Victoria and Albert Royal Yacht (‘HMY Victoria and Albert’ by the William Lind Collection is licensed under CC BY 2.0)

The King and Queen never failed to remember their debt to Annie for her care and skill during Edward’s ‘Coronation’ illness, according to the Cheltenham Examiner on the 12th of May, 1910:

KING EDWARD’S NURSE

‘…It was Nurse Fletcher’s untiring devotion during King Edward’s illness previous to his Coronation that won for her the appointment of Royal Nurse. Her skill on that occasion was fully appreciated by the late King, and both he and Queen Alexandra frequently referred to the services which Nurse Fletcher rendered in the sick room during those anxious weeks in the summer of 1902.’

It also brought her attention from certain quarters, as can be seen here in the Wigan Observer and District Advertiser on the 16th of July 1902, in which the Lady Mayoress of Liverpool herself is said to be asking after Annie:

‘The Lady Mayoress of Liverpool has been making enquiries with regard to Nurse Annie Fletcher, who is nursing his Majesty the King. It is interesting to note that Nurse Fletcher entered the Hospital for Women, Shaw-Street, Liverpool, in 1889, and was trained under Miss Carless. From August, 1893, to March 1896, she was charge nurse. She has been on the staff of Miss M’Coll’s [sic] Home in London, and nurse principally for Sir Frederick Treves.’

Queen Alexandra and Edward VII (‘Queen Alexandra and King Edward VII in Coronation Robes’ is licensed under CC BY 2.0)

In the wake of her nursing assistance to the King, she was considered of such public interest to the Nottinghamshire Evening Post that the occasion of her taking a holiday was deemed newsworthy:

‘Nurse Fletcher, one of the nurses who attended the King during his recent illness, is spending a holiday in her home at Ashton-in-Makerfield.’

Annie continued to receive this kind of recognition. In 1903, in the May edition of the magazine Girl’s Realm, as part of a series of articles authored by Miss Caroline Masters on ‘girls that the counties were proud of,’ a piece focused upon Lancashire, profiling the nurse. The edition itself was reviewed by the Wigan Observer and District Advertiser on the 29th of April, 1903:

Miss Fletcher, of Ashton.

‘Last of all the writer comes to the King’s nurse, Miss Annie Fletcher, whose father and family reside at Ashton, where she, too, is pleased to make her home when relaxation from duty permits. This is the reference:- “When, last June, King Edward VII was suddenly stricken down with illness, and the world paused aghast at the news, Lancashire was proud to know that one of the two nurses – Miss Annie Fletcher – chosen to nurse him had her home in its county.” A portrait is given of Miss Fletcher, as well as of Mrs. Banks, and most of the other Lancashire women whose excellences the article extols.’

In 1904, Nurse Fletcher had also taken on a role as head nurse in a newly-opened home caring for officers wounded during the South African War (Morning Post, 16th April 1904):

NURSING HOME FOR OFFICERS.

‘Miss Agnes Keyser, who, in conjunction with her sister, carried on such excellent work in Grosvenor Crescent nursing soldiers who had been wounded during the South African war, has now opened a similar home or hospital at 9, Grosvenor-gardens. By permission of his Majesty the home is to be known as King Edward VII’s Hospital for Officers, and the head nurse under Sister Agnes is Nurse Fletcher, who nursed the King in his illness two years ago.’

Annie’s work in the Royal Household was again brought to public attention following a ‘slight accident’ suffered by Edward whilst shooting at Windsor in 1905, reported by the Inverness Courier on the 21st of November, 1905:

NURSE FLETCHER.

‘King Edward’s slight accident at Windsor brought out a fact not generally known, that for some time past there has been a trained hospital nurse in constant attendance on his Majesty’s family and Household. The lady selected for this enviable position is one of two nurses who attended the King in his “Coronation” illness after his operation, the other nurse, Miss Haine, an Irish lady, being now matron of the Convalescent Home for Officers of the King’s Services at Osborne. Miss Fletcher, who is on permanent Royal duty, travels with the Queen and Princess Victoria, the rather delicate health of the Princess being possibly the reason for this arrangement. In having a nurse always at hand in case of sudden illness or accident, the King and Queen are following the example of the late Queen Victoria, who, for some time before her death, was accompanied by a trained nurse, as a sudden summons to a hospital or home for such an attendant might have caused great anxiety to the nation.’

It is also stated in the Staffordshire Advertiser (25th November, 1905) that without Nurse Fletcher’s ‘timely attention,’ the incident may well have been far more serious.

In that same year, she also nursed Princess Victoria through appendicitis, who, like her father Edward, was plagued by such episodes of poor health. This progress report in the Nottingham Evening Post on the 2nd of February 1905 names Annie in detailing the medical staff responsible for the Princess:

‘Her Royal Highness’s nurses are Miss Fletcher, who nursed the King after his operation and Miss Isaacs, both from Miss M’Caul’s home.’

In 1909, as recognition for her steadfast service, she was awarded the Royal Red Cross in the King’s Birthday Honours, as seen here in the Daily Telegraph & Courier (London) of the 9th November in that same year:

‘The King has been graciously pleased to confer the decoration of the Royal Red Cross upon Miss Annie Fletcher, who has been a hospital nurse for twenty years, in recognition of devoted service rendered by her to his Majesty and her Majesty the Queen since 1902.’

The Royal Red Cross (‘The Order of the Royal Red Cross and Bar’ by Robert Prummel is licensed under CC by 2.0)

The Wigan Observer and District Advertiser on the 13th of November 1909 also proudly announced the conferment of the honour upon their native resident, including the incidence of a public notation of her work in a speech given at a local school’s annual prize distribution:

KING HONOURS LOCAL NURSE.

MISS FLETCHER IN THE ROYAL BIRTHDAY LIST.

‘In the list of Birthday Honours, published on Tuesday, appears the name of Miss Annie Fletcher, of Ashton-in-Makerfield, upon whom the King has conferred the decoration of the Royal Red Cross, in recognition of devoted service rendered by her to his Majesty and the Queen since 1902. Miss Fletcher has been a nurse for the past twenty years.

PUBLIC REFERENCE AT PLATT BRIDGE.

The Chairman of the Hindley District Council, Mr. H. J. Bouchier, speaking at the annual prize distribution of St. Nathaniel’s Evening School, Platt Bridge, on Wednesday evening, said that in looking through the King’s birthday honours list, he saw the name of Annie Fletcher, who used to live not many miles from where they stood in that meeting, and he believed she went to school in that district. Miss Fletcher was one of the nurses to attend the King during his illness, and was very well thought of in the Royal Family. She had no more chances than the girls present that evening, possibly not as good, but by her own endeavours and ambition she had gone up from once place to another until she stood as high as any nurse in England could wish. (Applause). The girls present, he said, must not be disappointed if they could not become great nurses like Miss Fletcher, but they could all at any rate make the best of their opportunities. If they did not get to anything great they would be better men and women for having improved themselves. (Applause).’

King Edward VII was plagued by poor health. In March 1910, he contracted a chill whilst staying at Biarritz, and Annie was telegraphed for, immediately departing for the Continent. Her nursing skills were significant in his recovery, according to a report on Edward’s final year in the British Medical Journal of the 14th May:

‘On his way through France he caught a fresh chill, and during the early days of his stay at Biarritz his condition caused some anxiety. The skill of his physician and the care of his nurse, combined with the favourable influence of the climate, enabled him to shake off the enemy for a time.’

In April, the King fell seriously ill and Annie was immediately summoned to his bedside as someone who ‘understood his Majesty’s constitution probably better than any of his medical attendants’ (Wigan Observer and District Advertiser, 14th May, 1910):

NURSE FLETCHER AND THE KING’S ILLNESS.

‘Nurse Fletcher, of Bryn, who nursed the King through his previous illness was summoned to Buckingham Palace on Tuesday morning, last week, not Monday as previously stated. After being in attendance on his Majesty at Biarritz, Nurse Fletcher was taking a short holiday with her family in Bryn when she was summoned to the Palace. The first telegram was received at 7.23 on Tuesday morning: a second following an hour later at 8.25 and Nurse Fletcher left at 11.32 taking first available train to London.

The nurse summoned to his Majesty’s bedside was Miss Fletcher, who cared for him after the operation he underwent in the year of his accession and she was also at Biarritz during his first attack of bronchitis early in March. She is a[n]… expert in whom all the doctors attending the king have the most implicit reliance. Her Majesty also had the utmost confidence in Miss Fletcher, who, a contemporary states, understood his Majesty’s constitution probably better than any of his medical attendants.’

Despite Annie’s and the Royal Physicians’ best efforts, King Edward VII passed away at 11:30pm on the 28th April, having suffered a series of heart attacks.

The Funeral Procession of King Edward VII passing along Piccadilly (The Herald, 28th May, 1910)

Amidst the widespread newspaper coverage of the event, Annie herself was the recipient of a sizeable biography, again in the Wigan Observer and District Advertiser (14th May, 1910), demonstrating her status as a prominent figure among her local community in Wigan. I reproduce the account here in full as a manifestation of regional pride, even amongst so much national mourning:

KING EDWARD’S NURSE.

MISS ANNIE FLETCHER, R.R.C.,

OF WIGAN.

‘On page 3 will be found a portrait of Miss Annie Fletcher, King Edward’s nurse during his illness, wearing the decoration conferred upon her by the late King. Nurse Fletcher, who has had the great honour of occupying the distinguished position of Royal nurse ever since King Edward came to the throne is, it is interesting to note, a native of Wigan, having been born in the Gidlow district [sic]. Some twenty years ago her parents removed to Brynn, and took up residence in Wigan-road, her father being an under-manager under the Garswood Hall Colliery Company.

Nurse Fletcher’s career reflects the greatest credit not only on herself but on the profession to which she belongs. At first the was associated for several years with the Hospital for Women in Shaw-street, Liverpool, and before joining the staff of the nursing home under Miss Ethel M’Caul, R.R.C., she held other nursing appointments, among these being that of matron of a small hospital. She had so perfected her training in the profession she adopted that she was able to become associated with the King Edward Hospital, Grosvenor Gardens, London, with which the Royal physicians were identified, and in this way she became the King’s nurse.

It was shortly before the date fixed for the King’s Coronation when his Majesty was seized with a sudden illness, and the operation for appendicitis was so skilfully performed that Nurse Fletcher was brought into close nursing association with Royalty. She was then placed by Sir Frederick Treves as second nurse to the King, and so greatly were her services appreciated that she was later taken into the Royal household as a permanent nurse. In this way was her skill and devotion recognised. When the King journeyed to Biarritz on his last visit, it was Nurse Fletcher who was chosen to be in attendance upon his Majesty, and when the King returned to London she was granted a week’s holiday, when she came on a visit to her relatives and friends in the Wigan district.

Miss Fletcher’s mother is dead, and it was while taking this holiday, staying with her father at Brynn, that the telegram asking her to return to Buckingham Palace was received. This was on Tuesday morning, and Nurse Fletcher made all haste, taking the first available train to London, and she was in constant attendance in the Royal apartments until the King passed away.

Nurse Fletcher’s services, it is interesting to note, have received Royal recognition. She was honoured with the Order of the Red Cross in King Edward’s birthday list last year, and she has received many presents, most of which bear touching inscriptions, from various members of the Royal Family. When she was chosen as a Royal nurse her appointment at Court was duly gazetted.’

As noted above, Annie’s father and family had later returned to the Wigan area from Flintshire, settling in Brynn. In 1901 they were living at 343 Wigan Road with William taking up the position of Under-Manager (Below Ground) at the Garswood Hall Colliery Company. Annie’s mother had by this time died and William was living with his three sons, all of whom were employed in the business of coal – Robert, 28, as a Hewer, Thomas, 21, as a Colliery Wagon Shunter (Above Ground) and Harry, 19, also as a Hewer. The family’s increased wealth and status, as well as the loss of Sarah, had also brought about the employment of a domestic housekeeper. In 1911, William had retired and was living with his son Robert, a coal salesman, and the latter’s wife Hannah. The couple had three children, one of whom was named Annie. It is not inconceivable to surmise that, following Annie’s newfound fame for her part in attending to Edward on his deathbed, her brother wished to honour his sister with this familial gesture, perpetuating her memory through this expression of pride and satisfaction at her achievement. Annie herself had never married and remained childless, meaning that such a move must have been especially meaningful to her.

The local zeal generated by these connections had led not only the Wigan Observer and District Advertiser (as seen above), but also a number of other publications to falsely attribute Annie’s birthplace to Wigan, a state of affairs corrected by a letter to the editor of the Yorkshire Post on the 13th of May 1910:

THE KING’S NURSE.

TO THE EDITOR OF THE YORKSHIRE POST.

Sir, ‘ The other day there appeared in one of the Wigan newspapers an account of the life of Nurse Fletcher, who was in attendance upon our late King during his last illness. This paragraph stated that Nurse Fletcher was born at Wigan. Her friends at Beeston wish me to state that she was born at Crow Nest Lane, Beeston, and is descended from an old Beeston family. Your readers may be interested to know that Leeds has the honour of being the birthplace of the nurse that has been so much valued by our Royal Family in their sickness – Yours, etc.,

W.L.INGLE.

Millshaw, May 12.

In a later report published in the British Medical Journal and referred to above (May 14th, 1910), Annie Fletcher is singled out as being instrumental in Edward’s care, in company with the King’s Physicians:

‘The King was attended throughout by his Physicians-in-Ordinary (Sir Francis Laking, Sir James Reid, and Sir Douglas Powell), and by one of his Physicians Extraordinary (Dr. Bertrand Dawson). Dr. St. Clair Thomson being called in consultation some time ago, his Majesty underwent a course of vaccine treatment at the hands of Dr. Spitta, bacteriologist at St. George’s Hospital. All the resources of modern science were used in the last illness. He was nursed by Miss Fletcher, whose ministrations he had learned to appreciate at the time of the operation performed upon him by Sir Frederick Treves.’

Throughout the nation, Nurse Fletcher was cited in a great number of regional newspapers, thanking her for her attendance upon Edward prior to his death, as seen here in the Clifton Society on the 12th of May, 1910, a Bristol publication:

THE ROYAL NURSE.

‘Many kindly thoughts, will, says The Globe, be turned to Miss Fletcher, who nursed King Edward through that illness which fell with such dramatic suddenness on the eve of his Coronation, and who brought all her skill and tenderness to the Royal bedside in the last and fatal hours. Miss Fletcher had become a part of the Royal household, respected and honoured by all who have been associated with her. Her exalted patient had the greatest regard for Nurse Fletcher, and not long ago bestowed upon her the decoration of the Royal Cross.’

In 1912, on the two year anniversary of the King’s death, Annie was even invited to a private service attended by members of the Royal Family in the Albert Memorial Chapel, Windsor, to celebrate Edward’s life.

Indeed, Annie had remained close to the family. After Edward’s passing, she had continued as nurse for Queen Alexandra until the latter passed away in 1925. The following image from The Sphere on the 5th of December in that same year depicts the deathbed scene shortly after the Queen had passed away. Nurse Fletcher had been in constant attendance on her since her ill-health had forced her to retire to Sandringham House. Annie is shown at her bedside in the right-hand corner of the illustration, tentatively drawing the curtain back.

Annie subsequently retired to Lancashire, a lifetime’s dedicated service behind her. She took up residence in Heeley Road in the seaside resort of St. Anne’s on Sea, in a house whose name consisted of a royal acronym expressing her great love of this family to whom she had given so many years of her life – “Vedal” (V for Victoria, ED for Edward and AL for Alexandra).

Lytham St. Anne’s and its Promenade (‘The Promenade at Lytham St. Anne’s’ by Raymond Knapman is licensed under CC BY 2.0)

She remained close with the Royal Family, as is noted in her obituary printed in the Manchester Guardian on the 15th of May 1933, with Princess Victoria even reported to have stayed with her on a number of occasions:

A ROYAL HOUSEHOLD NURSE

‘Miss Fletcher nursed the late King Edward when he had appendicitis. She remained with the royal family and nursed Queen Alexandra up to the time of her death, when Nurse Fletcher retired as nurse from the royal household. She was awarded the Order of the Red Cross in 1910 [sic]. Princess Victoria, who frequently visited her at St. Anne’s, has telegraphed her sympathy with the family.’

Princess Victoria (‘Princess Victoria of the United Kingdom, daughter of Edward VII’ by W. & D. Downey is licensed under CC BY 2.0)

These visits of Princess Victoria to the nurse were later recalled the former had passed away, detailed here in the Lancashire Evening Post on the 3rd of December, 1935, two years after Annie herself had passed away:

TO SEE OLD NURSE.

Princess Victoria’s Visit to Fylde Recalled

‘The death of Princess Victoria (as reported on page 3) recalls visits which Her Royal Highness paid some years ago to Lytham St. Annes, when, as an incognito visitor she stayed with a former nurse of the Royal Family in Heeley-road.

Princess Victoria at that time stayed with Nurse Fletcher , who had been a servant of the Royal Household practically all her life. While staying there Princess Victoria planted a small beech tree and inscribed certain markings on a window of the house as souvenirs of her visit.

The beech tree remains, but the window was removed by relatives of Nurse Fletcher when she died about two years ago.

It is also understood that while on visits to the Fylde Princess Victoria visited relations of Nurse Fletcher living at a house in North Shore, Blackpool. Few people, however, were aware of her visit there on account of the strict secrecy which was maintained.

Mr. H. Mosscrop, a newsagent, of Headroomgate-road, St. Anne’s, speaking to our reporter to-day, recalled Princess Victoria’s visit to the town. “She was often seen walking around here, and frequently came into the shop,” he said, “but it was not until later that we realised who our distinguished visitor was.”‘

Annie herself had been taken ill with pneumonia in 1933, whilst staying with her sister Mary in Peacefield, Marple. She passed away at the age of 68 on the 13th of May and was buried in the churchyard at All Saints on the 16th of that same month.

All Saints Churchyard, Marple – Image by A Grave Announcement

Upon death, she left a considerable estate amounting to around £100,000 in today’s money, according to the Dundee Evening Telegraph on the 5th of September 1933:

‘Nurse to King Edward, Miss Annie Fletcher, of Heeley Road, Lytham St Anne’s, left £1968.’

In addition to this monetary sum, she also bestowed a watch given to her by King Edward VII upon her nephew, as reported in the Lancashire Evening Post on the 4th of September 1933:

ROYAL NURSE’S WILL

Watch Presented by King Edward to Lytham Woman

‘Miss Annie Fletcher, R.R.C.O., Vedal, 150 Heeley Road, Lytham St. Annes, for many years a nurse in the Royal household and nurse to King Edward VII, when he was operated upon for appendicitis and during his last illness, and who died on May 13th last, aged 69 [sic] years, left estate of the gross value of £1,968, with her personalty £1,921.

She left to her nephew, the Rev. Harry Fletcher, the gold watch presented to her by his late Majesty, King Edward VII; and one year’s wages to her maid, Harriet Mainwaring, if in service at her death.’

This timepiece was one of a number of gifts presented to Annie by the Royal Family, the rest of which were sold at Bonhams in 2003.

Nurse Fletcher’s death had been reported in a wide variety of regional newspapers, from Scotland to Southern England, signalling the continuing interest in the nurse whose name, at the height of her fame, was known throughout the nation. Ultimately, her life stands as a remarkable exercise in social mobility as coal-miner’s daughter rose to become Royal Nurse to King Edward VII, an extraordinary achievement for an extraordinary woman, and a fitting voice for 2018’s celebratory year of Extraordinary Women.

A Grave Announcement (@AGraveAnnounce)

With thanks to the profile of Annie Fletcher’s life by the Marple Local History Society for additional background information.