What a lesson in the tawdriness of all our worldly wealth and earthly ambition does a visit to the old Necropolis afford.’

Glasgow Herald, 14th October 1892

On a balmy July afternoon, I found myself on the path meandering its way towards the summit of the Glaswegian Necropolis. Towering above the cathedral, this spectacular array of funerary monuments is a striking fixture in the skyline of the city. On this day, the weather was capricious and temperamental. In one sphere of the sky, the clouds loomed low, glowering menacingly. Elsewhere, wispy cumuli drifted shapelessly across the cerulean heavens.

Image by A Grave Announcement

Upon entry, I passed through a pair of gilded cast iron gates, a beautifully formal way to make one’s acquaintance with a Victorian cemetery.

Image by A Grave Announcement

After crossing the so-called ‘Bridge of Sighs’ (designed by Glaswegian architect David Hamilton in 1833 in a homage to its Venetian namesake, and traversing the covered stream of the Molendinar Burn, colloquially known as ‘The Styx), scene of many a sombre funeral procession, I took the left path away from the façade of the imposing central archway that divides the route into its two branches. The hill began to ascend, a steep climb but not breathlessly so, the sinuous roaming of its path lined with a miscellany of sepulchral stones, and the layout, lacking a scrupulous and exacting blueprint, charmingly organic. More than 50,000 souls have found their final resting place in this location, and it is difficult not to feel like something of an intruder into their eternal peace when traversing these streets, bringing the land of the living to the city of the dead.

The foundation stone of the Necropolis was laid in 1826, its inaugural interment taking place in May 1833. This occasion was the burial of ‘the Jew Joseph Levy,’ a sixty-two year old quill merchant who had been struck down by cholera. The expanse chosen for the city of the dead had formerly been the Merchants’ Park, an area once bedecked with needled firs, and followed by the languid gestures of planted willows and elms. The transformation of this tract into a place of rest, proposed by John Strang, Chamberlain of the Merchants’ House, was entrusted to a competition launched to find the best design. The work of the winner, David Bryce, was amalgamated with that of four other entrants by the judges and George Mylne was appointed as Superintendent to oversee the execution of the proposed outline, a schematic inspired by the Parisian garden Necropolis Père Lachaise. This spirit of collaboration, of resources combined, can be felt in the eclectic conglomeration of the stone requiems to the dead that came to ordain the place, the finished product a visual representation of our own collective cultural memory, a history no longer merely peopled by the forgotten dead.

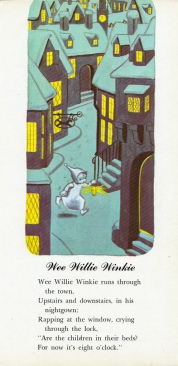

As I ambled along the track, my attention was drawn to a rather well-kept monument. Despite not serving as the largest or most imposing of the reliquaries, the obelisk seemed to loudly announce its presence. Its grey surface was speckled and pockmarked, like skin chapped by the wind. The man’s face carved in relief was quietly reflective, seeming to look away from the hill itself and gaze across Glasgow at the city he had left behind. The memorial was crowned by the engraved emblem of a harp and laurel wreath, Apolline tokens of creative endeavour, symbolising the man’s literary craft. Monumentalising a staunch Glaswegian, whose work has taken on global importance, resonating across the decades, in inspecting the monument it seemed as if I could hear the famous verses being spoken, that masterful Scotch dialect crying in the wind: Wee Willie Winkie runs though the town…

Image by A Grave Announcement

I am speaking, of course, of William Miller, a literary giant, whose death, wretched and in penury, saw the man consigned to the oblivion of an unmarked grave in Glasgow’s Tollcross Cemetery, a state of affairs later rectified by his friends and admirers in financing this lapidary ode to the great man. The inscription reads:

To the Memory of William Miller

The Laureate of the Nursery

Author of Wee Willie Winkie

Born in Glasgow August 1810

Died 20 August 1872

Born in the Bridgegate area of Glasgow, a formerly prosperous merchant district then experiencing a slum-like decline, William Miller spent most of his formative years in the East End of the city, coming of age in the village of Parkhead. Plagued by ill health as an adolescent, he was unable to fulfil his aspiration of becoming a surgeon and settled instead for life as a wood-turner, undergoing an apprenticeship in that skill before achieving great expertise in the intricate craft of cabinet-making. As a youth, he published a number of pieces in various newspapers which, sadly, do not survive. His first poetic appearance was in Whistle Binkie: Stories for the Fireside, a compendium of songs edited by Mr David Robertson in 1841. It was the publication in this volume of the nursery song Wee Willie Winkie, however, the grumpy figure personifying sleep, that brought him fame and admiration, although at first it was received with mixed opinions by Robertson’s friends. To settle the dissent, he dispatched the manuscript to Mr Ballantine of Edinburgh (who had himself contributed much to the publication) who asserted, according to the Perthshire Advertiser on the 29th August 1872) that:

“There is not at this moment in the whole range of Scottish songs, anything more exquisite in its kind than that little Warlock of the Nursery, “Wee Willie Winkie.”

This achievement eventually commanded the attention of such literary connoisseurs as Lord Jeffrey, founder of the prestigious Edinburgh Review. Such notice notwithstanding, William Miller abnegated the kind of literary relationships which were based upon patronage, choosing to hone his craft at home when the honest labour of the day was done. Indeed, such was the hardship he underwent as a consequence of his trade that it was reported by the Glasgow Herald on the 6th February 1846 that the Countess of Selkirk, an admirer, had transferred to the poet the sum of two pounds following a period of ill-health in which he was unable to work:

“We learn that the Countess of Selkirk has transmitted to Mr David Robertson of this city, by the hands of the Rev.Mr Underwood of Kirkeudbright, the sum of £2, for behoof of William Miller, the author of “Wee Willie Winkie,” &c.; her Ladyship having been impressed with a favourable opinion of the poet from having perused his Nursery Rhymes. Mr Miller is so much improved, that he is now able to pursue his occupation of a wood-turner.”

The widespread recognition of this talented literary craftsman all took place before William Miller had even published a collection of his works. In fact, this did not occur until 1863, when, prevailed upon by a number of friends, he circulated the volume Nursery Songs and other Poems, an enormously popular offering at the time. This treasure trove was dedicated ‘to Scottish mothers, Gentle and Semple…not fearing that, while in such keeping, they will ever be forgot.’ It included the original Scots version of ‘Wee Willie Winkie,’ a rhyme anglicised very soon after its publication:

“Wee Willie Winkie” by Thoth, God of Thor is licensed under CC by 2.0

Wee Willie Winkie runs through the toon,

Up stairs and doon stairs, in his nicht-goon,

Tirling at the window, cryin’ at the lock,

Are the weans in their bed, for it’s now ten o’clock?

Hey, Willie Winkie, are ye coming ben?

The cat’s singing grey thrums to the sleeping hen,

The dog’s spelder’d on the floor, and disna gie a cheep,

But here’s a waukrife laddie that winna fa’ asleep.

Onything but sleep, you rogue, glow’ring like the mune,

Rattling in an airn jug wi’ an airn spoone,

Rumbling, tumbling round about, crawing like a cock,

Skirlin’ like a kenna-what, wauk’ning sleeping fock.

Hey, Willie Winkie – the wean’s in a creel,

Wambling aff a bodie’s knee like a very eel,

Ruggin’ at the cat’s lug, and raveling a’ her thrums-

Hey, Willie Winkie – see, there he comes!’

Wearied is the mither that has a stoorie wean,

A wee stumple stoussie, that canna rin his lane,

That has a battle aye wi’ sleep before he’ll close an ee

But a kiss frae aff his rosy lips gies strength anew to me.

In that same volume, we revel in the jubilant celebrations of Hogmanay, commemorate a marriage, wonder at the effect of a sudden flurry of money in the form of an inheritance, list the virtues of ‘my poor old coat,’ and are introduced to the figure of Jack Frost, the hoar-breathing rover whose advent betokens the arrival of spring.

“Jack-frost” by Polylerus is licensed under CC by 2.0

In November 1871, an ulceration of the leg forced William to cease his trade. Despite the increasing frailties of his body, his mind remained as sharp as ever and he continued to write and disseminate poetry, works which appeared in publications such as The Scotsman. Learning of his condition as an invalid, The Greenock Telegraph and Clyde Shipping Gazette on the 1st March 1872 urged its readers to furnish monetary contributions ‘for this deserving old poet:’

WILLIAM MILLER THE POET.

“Perhaps the most delicious nursery song that has been written by a modern minstrel for the delectation of the “bairns” in these northern regions is the song of “Wee Willie Winkie.” We are sorry to hear that the writer of it has for a long time past been an invalid, and that he is in poor circumstances. William Miller has a strong claim on the public for some help to smooth his declining years. He is now upwards of sixty, and at his advanced age, afflicted as he is with serious disease of the limbs, there is no prospect of his ever being able again to resume work. By trade he is a wood turner, and he resides in Glasgow, of which city he is a native. One who knows him says that his heart seems still young, his mind still vigorous; but he feels his position irksome and his spirit galled that he cannot now, as formerly, earn by the swear of his brow the bread of independence.”

The following July, he repaired to Blantyre, hoping that the town’s airs – the settlement was 8 miles from Glasgow – would reinvigorate him. The sojourn proved futile and he was soon returned to his son’s house in the city, having suffered a paralysis of the lower limbs. He passed away, destitute, at the age of 62 on the 20th August, 1872.

The poet subsequently received a number of obituary notices in the newspapers lamenting the loss of this Scottish talent. The account below, in The Greenock Telegraph and Clyde Shipping Gazette on the 22nd August, 1872), reports the grim news:

DEATH OF WILLIAM MILLER, THE POET

“The death is announced of William Miller, the nursery poet. He was born in Glasgow in August, 1810. He was early apprenticed to a wood turner, and by diligent application to business made himself one of the best workmen of his craft; and even in his later years there were few who could equal him in the quality of his work. It is, however, as a poet that he is known to fame. In his early youth he published several pieces in the Day and other newspapers; but from the fact that no record of these productions was observed, it is impossible to know when they issued from his pen. The first thing that brought him into public notice was the publication of the nursery song “Willie Winkie.” The MS. of this song was sent to Mr. Ballantine in Edinburgh, who gave it unqualified praise, as being the very best poem of its kind that he had ever seen. This led to the publication of the poem, and it at once attracted a large amount of attention. This was followed by a number of other pieces of a similar description, all of which were received with great favour, and led to the author’s acquaintance with Lord Jeffrey and other gentlemen of literary tastes. The best of his nursery songs which have obtained for him the well-earned title of the Laureate of the nursery were all written before he was 36 years of age; but it was not till 1863 that, at the request of several friends, he collected together and published a small volume, entitled “Nursery Songs and other Poems.” It had a wide circulation and has earned for the author a reputation that will never decay.”

Most fulsome in its praise of the deceased was the sketch authored by Robert Buchanan in the St Paul’s Magazine (reproduced here in The Greenock Telegraph and Clyde Shipping Gazette on the 22nd August 1872), emphasising the global appeal of William’s work – songs now sung from Canadian Manitoba to the sonorous banks of the great Mississippi river:

“St Paul’s Magazine for July contained a notice of Wm. Miller, written by Robert Buchanan, who only knew the subject of his sketch through his writings. He had expressed a desire to make Wm. Miller’s acquaintance, and had arranged to call on him on his first visit to Glasgow, but the death of the poet has prevented that wish being gratified. In the article alluded to Mr Buchanan says – “No eulogy can be too high for one who has afforded such unmixed pleasure to his circle of readers; who, as a master of the Scottish dialect, may certainly be classed alongside of Burns and Tannahill; and whose special claims to be recognised as the Laureate of the Nursery have been admitted by more than one generation in every part of the world where the Doric Scotch is understood and loved. Wherever Scottish foot has trod, wherever Scottish child has been born, the songs of Wm. Miller have been sung. Every corner of the earth knows ‘Willie Winkie’ and ‘Gree Bairnies, Gree.’ Manitoba and the banks of the Mississippi echo the ‘Wonderfu’ Wean’ as often as do Kilmarnock or the Goosedubs. ‘Lady Summer’ will sound as sweet in Rio de Janeiro as on the Banks of the Clyde.” Again – ‘Few poets, however prosperous, are so certain of their immortality. I can scarecely conceive of a period when William Miller will be forgotten; certainly not until the Scotch Doric is obliterated, and the lowly nursery abolished for ever. His lyric note is unmistakeable – true, deep, and sweet. Speaking generally, he is a born singer, worthy to rank with the three or four master-spirits who use the same speech; and I say this while perfectly familiar with the lowly literature of Scotland, from Jean Adams to Janet Hamilton, from the first notes struck by Allan Ramsay down to the warblings of ‘Whistle Binkie.’ Speaking specifically, he is (as I have phrased it) the Laureate of the Nursery, and there, at least, he reigns supreme above all other poets, monarch of all he surveys, and perfect master of his theme. His poems, however, are as distinct from nursery gibberish as the music of Shelley is from the jingle of Ambrose Phillips. They are works of art – tiny paintings on small canvas, limned with all the microscopic care of Meissonier. The highest praise that can be said of them is that they are perfect ‘of their kind.’ That kind is humble enough; but humility may be very strong, as it certainly is here.'”

The news of William Miller’s expiration spread beyond Scotland. The Christchurch Times of Hampshire included a brief notation in its edition on the 31st August 1872:

“The death is announced of William Miller, the nursery poet. Born in Parkhead, in August, 1810, William Miller spent his earliest days in the village, and thereafter resided in Glasgow.”

Similarly, the Cheltenham Chronicle on the 10th September 1872 reported on the event:

“The death is announced of William Miller, the nursery poet. Born in Parkhead, in August, 1810, he subsequently resided in Glasgow. He was author of Wee Willie Winky [sic] and other well-known rhymes.”

William Miller was interred in an unmarked grave near the main entrance to Tollcross Cemetery, a state of affairs over which a great clamour arose, with friends and supporters condemning the inglorious and wretched resting-place of this immortal poet. A campaign was even spearheaded by the Telegraph and Clyde Shipping Gazette, a plea to its readership which descended into sniping bitterness against the merchant class for their perceived meanness in the strength of their donation, as can be seen in the edition on the 29th July 1872:

“There has been a great deal of writing in favour of the proposal to get up a testimony for William Miller, the “laureate of the nursery,” writer of “Wee Willie Winkie” and other immortal lyrics. A brief appeal of our own was not fruitless, provoking at least one handsome subscription, that from Mr Thallon of London; but we regret to say that the merchant princes of Glasgow are contributing (if they contribute at all) on a scale which does not say much for their appreciation of poetry. The great firm of Messrs J. and W. Campbell & Co., one of whose members gave 200 guineas to the Norman Macleod Testimonial, gives to the poor old poet the munificent sum of – twenty shillings! Messrs J. Tennant and Co. also give a pound. In fact a pound seems to be the maximum subscription. And the bard, besides being a genuine poet, has been all his days a decent, hard-working, God-fearing man – paying his way, and even when laid aside by illness asking nobody to help him – nay, so independent in spirit that he begged his friends to make no appeal on his behalf. To this true poet and true man, in his day of trouble, when he can no longer work for his bread. The merchant princes of Glasgow throw a contemptuous trifle which would not keep them in brandy and soda for a day. On the whole, we should prefer to see them give nothing.”

The proposed monument was eventually erected by public subscription through such calls for contributions.

William Miller’s reputation remained that of a consummate and skilled poet throughout the 19th century. Indeed, The National Dictionary of Biography (Vol.13) spoke of the man as follows:

“He has an easy mastery of the Scottish dialect; his sense of fitting maxim and allegory is quick and trustworthy, and his lyrical effects are much helped by the directness and simplicity of his style.”

It was particularly the cultural influence of William Miller’s most famous creation, the figure of Wee Willie Winkie, that had a sizeable impact. Indeed, the character was immortalised further through Rudyard Kipling’s inclusion of the figure in his 1888 Wee Willie Winkie and Other Child Stories, and, in 1937, an eponymous adventure film starring Shirley Temple was made for the big screen.

“Cover_to_Wee_Willie_Winkie”

“Cover_to_Wee_Willie_Winkie”- by University of California Libraries

- is licensed under CC BY 2.0

The German-American painter Lionel Feininger unveiled the cartoon strip “Wee Willie Winkie’s World” in the Chicago Tribune on August 19th, 1906 and this continued in print until February 17th, 1907. Salman Rushdie’s 1981 novel Midnight’s Children, includes the character “Wee Willie Winkie,” a minstrel, in homage to William Miller’s creation.

In 2009, Glasgow City Council unveiled a tribute to the poet at his former dwelling, 4 Ark Lane in Dennistoun, erecting a bronze plaque on the wall of the Tennent’s Brewery which now sits on the site of William Miller’s house. A blue plaque in the Trongate also serves as a quirky tribute to his most famous creation, declaring that ‘Wee Willie Winkie was spotted here in his nightgown’ in 1841.

It is clear that, even now, William Miller’s pyjama-clad figure still urges children to get into their beds and sleep as a nursery song learnt and replayed the world over, one of a number of figures invoked by parents at bedtime, such as Germany’s Das Sandmännchen and Denmark’s Ole Lukøje.

I fondly remember the Necropolis from my visit to Glasgow almost twenty years ago. I stayed in a B&B practically across the street. Great location!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That sounds like an amazing trip – it’s so nice to hear your memories of the area. Hope you enjoyed the post!

LikeLiked by 1 person