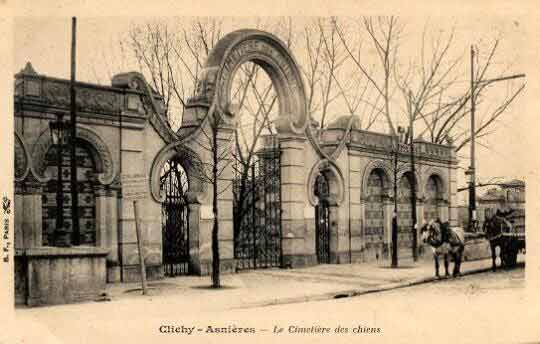

In 1899, the Cimetière des Chiens et Autres Animaux Domestiques (Dogs and Other Domestic Animals Cemetery) was officially opened on the Ile des Ravageurs, near Asnières, a north-western suburb of Paris. Designed in the style of an elaborate necropolis, with imposing Art Nouveau entrance-gate in marble and an array of ornate, neo-classical monuments, many beloved pets went on to be entombed there.

Cimetière des Chiens et Autres Animaux Domestiques by Brito MA is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Forget Père-Lachaise, this zoological cemetery even hosted the remains of famous animals such as Rin Tin Tin, the male German Shepherd rescued by American Corporal Lee Duncan from a World War I battlefield at St. Mihiel. The dog became an international superstar after starring in twenty-seven motion pictures.

Poster for the American Film ‘Where the North Begins’ (1923) by We Hope is licensed under CC BY 2.0

When Rin Tin Tin passed away in 1932, his owner, struggling to finance an appropriate funeral for his companion, sold his house and used the funds to repatriate the animal’s body to his native France in a poignant expression of the bond between owner and pet. Finding his final resting-place in the area of the cemetery reserved for dogs alone, Rin Tin Tin lay buried amidst a host of other stones inscribed with such epitaphic asides as Voltaire’s ‘Le chien c’est la vertu, qui ne pouvant se faire homme, s’est fait bête (the dog is virtue – unable to be a man he made himself a beast),’ and the French poet Alphonse de Lamartine’s verses ‘mets ton coeur pres du mien. Et seul pour nous amers, amons nous, pauvre chien (place your head near mine, as none remained to love me, so let us love each other, my poor dog).’

©Paris Adele

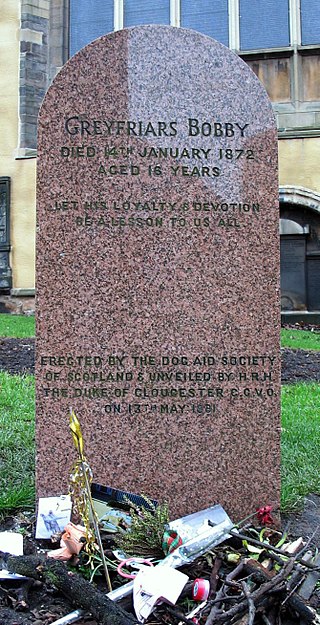

There were, of course, more than just notable canines laid to rest at Cimetière des Chiens et Autres Animaux Domestiques. A leisurely wander around the site’s environs reveals a veritable menagerie of honoured creatures: cats, horses, monkeys, sheep, fish and hens. It is clear that the commemoration of animals had become an important facet of how we conceptualise our relationship with the dead, and, deceased, they were often accorded funeral and sepulchral accoutrements equal to, or even exceeding, those assigned to kin. Indeed, another renowned canine, the Skye Terrier Greyfriars Bobby (1855-1872), a pet whose loving devotion towards his deceased owner in spending the rest of his life sitting on the latter’s grave ensured that the dog himself was accorded similar obsequies to those of his master, receiving burial within the same churchyard. Whether apocryphal or historical fact, the enduring nature of the story speaks to something in the human condition, forcing us to reflect upon how we conceptualise mortality and to enter into the dialogue between animal and man. Indeed, the commemorative statue in Edinburgh, its nose stroked for luck by visiting tourists, is an excellent example of the need to monumentalise the relationship between animal and man.

Statue of Greyfriars Bobby by Michael Reeve is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Bobby’s Headstone in Greyfriars Kirkyard by Stephen Montgomery

During this late nineteenth-century period in which the Parisian animal cemetery was born, pet funerals became all the rage, a sepulchral fad found not only amongst those in Europe, but also in the United States. Indeed, in 1881 the Hyde Park Dog Cemetery in London opened its doors, receiving animals for interment, crowned by miniature headstones, until 1903.

Hyde Park Dog’s Cemetery by Leonard Bentley is licensed under CC BY 2.0

The site was subsequently followed in 1896 by New York’s Hartsdale Canine Cemetery, the oldest and largest in America. The latter burial ground now contains the remains of over seventy thousand animals.

Entrance to Hartsdale Pet Cemetery by SteveStrummer is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Despite the presence of former pets inhumed relatively cheaply in ‘common graves’ on sites such as the Cimetière des Chiens et Autres Animaux Domestiques, the bestowal of these resting-places upon treasured pets was, more often than not, the preserve of the elite and well-heeled, individuals who often chose to mourn their loss by means of complex and elaborate funeral ritual, proceedings involving the use of the myriad trappings of the dead. Indeed, it was widely reported in 1901 that a young Parisian woman spent 6000 francs on a monument erected for her pet pug. Such activities were frequently documented in local and national newspapers, where the tone taken was one of a whimsical look at the endearingly odd, an approach simultaneously exuding a marked poignancy, conveying the sense of powerful fascination often felt by those present, drawn into the unexpected through the familiarity of funeral ceremony marking the passing of the dead. Such accounts carefully relate the opulence of these affairs, noting in detail the appearance of coffins and tombs and the disjunctive nature of the seemingly anthropomorphic rendering of the pet in state. In 1897, for instance, the 26th of June edition of Pearson’s Weekly narrates an American woman’s loving remembrance of her deceased Skye terrier, events for which money was clearly no object.

HER DOG’S FUNERAL.

The other day an American woman doctor gave an unusual dog funeral to her Skye terrier, that died after a career of fifteen years. She had the dog embalmed, and he lay in state for one whole day until the crowd became so large and unruly that the door had to be closed.

The coffin was made by his mistress’s own hands. It was covered with white material and trimmed with ribbons. It rested on a large pedestal, at the foot of which was a vase filled with roses, which was placed on the dog’s grave.

The dog’s head rested upon a pillow of white crépon, edged with lace and surrounded by flowers. The funeral took place in the afternoon. Interment was in the rear of Baltimore cemetery, where a tombstone will be erected to the animal.

The splendour and grandiosity of such occasions is seen again in this account in the Edinburgh Evening News of the 11th of December, 1879, detailing the caprice of human behaviour, rather unsympathetic to the feelings of the bereaved owner:

…to furnish a rich cloth-covered casket, with velvet trimmings and solid silver plate and handles. The interior of the casket was to be lined with white satin and silk trimmings. All this was for a dead dog belonging to a wealthy family up town. The animal had been nursed and taken care of for the past 20 years. The dead animal lay in the casket wrapped in a mantle of white satin, with white silk ribands around the neck. The remains were taken to a cemetery close to New York and put into the family vault. Six carriages, containing the friends of the dog, followed the remains to the cemetery. What next?

Sometimes a tale of canine burial, embarked upon with an air of underlying contempt, as above, took a moving turn, steeped in pathos, as seen in a report from New York in the Shields Daily Gazette of the 18th of October, 1900:

A New York paper thus describes the funeral ceremony which obtained in connection with a pet dog named Booby, belonging to a Mr Seeberger. The latter, it was said, had a coffin made by a local undertaker, and arranged funeral ceremonies with a procession and band. The coffin, covered with flowers, was placed in a child’s express wagon , drawn by two of Mr Seeberger’s boys. Otto Clanberg and Eugene Branenstein walked beside the waggon as pall-bearers. At the grave the coffin was lowered into the ground as the band played “The Watch on the Rhine.” Adolph Schnackkenberg delivered an oration in which he eulogised the dead dog and his many excellent traits. While the grave was being filled Mr Seeberger wept. He said he felt as bad as if he had lost a child , for Booby was a dog faithful and true.

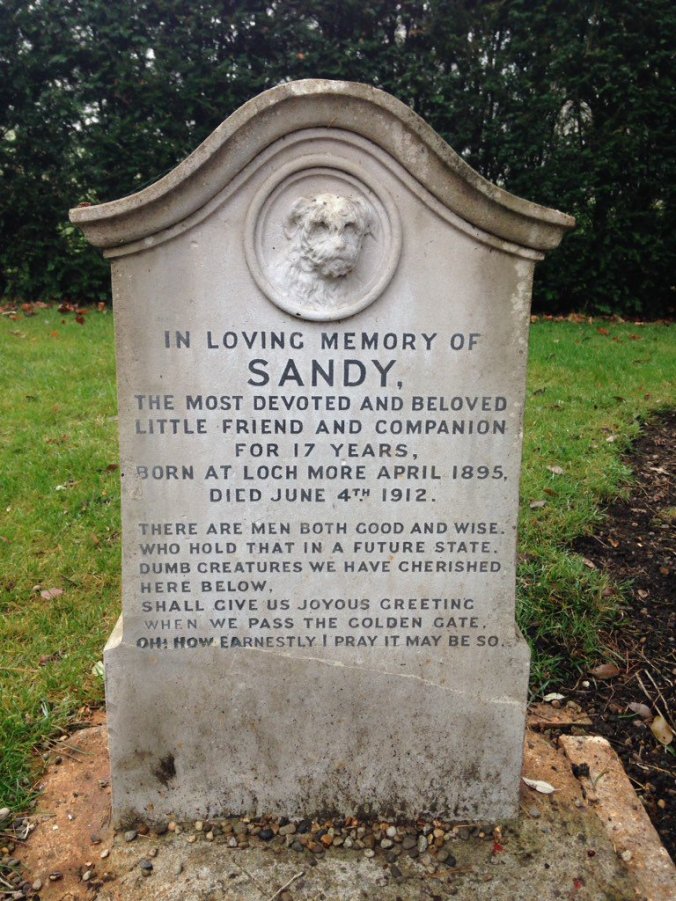

The grave of Sandy at Kilkenny Castle, whose owner was Arthur Butler, the 4th Marquess of Ormonde and his wife Ellen Stager (© Reddit)

Such need to celebrate canine fidelity and dedication underscores the following account, taken from the Daily Gazette for Middlesborough of the 11th of December, 1879:

A DOG’S FUNERAL.- New York has just witnessed a strange funeral. A Mr Wilmarth of that city had for twenty-three years owned a large Newfoundland dog which some long time ago saved his wife from drowning, and upon the animal the aged couple, having no family, lavished all their affection. At length the dog died from fulness [sic] of days, whereupon an undertaker was ordered to make a coffin for it , and to place upon the casket a silver plate. The remains being thus decently packed, two carriages escorted them to Greenwood Cemetery, where in the Wilmarth family plot the dog was buried. A headstone is now to be set up over the place detailing the virtues of the faithful creature departed , as a monument of its worth and a record of its owner’s gratitude.

That the deployment of such ceremonial flair particularly in regard to man’s best friend was an apt reflection of the zeitgeist is made clear in this brief report from the Gloucestershire Echo twenty years later (22nd of March, 1899):

Dog’s funerals form the latest American fashionable craze. On Tuesday a Mrs Leach, of New York, held a funeral with a hearse and two coaches. The well-known financier, Mr Pierpont Morgan, whose bulldog had a glass eye, also gave a funeral. Something of a scandal occurred recently, when a Mrs Fish endeavoured to bury her dog in Long Island Cemetery. The pastor successfully opposed the interment.

Arrangements were not only made as far as the pet’s body was concerned. At the very beginning of the twentieth-century, the Dundee Evening Post (29th May, 1901) relayed the news that a distinctive commemorative practice had developed in the pet bereavement world, emerging from the ritualistic behaviours surrounding elite deaths:

It is now the custom in fashionable society to send around death notices of pet dogs on black-bordered paper which read about like this: –

“Overwhelmed with grief, we inform you of the departure of our dearly-beloved and faithful Loulon. His earthly remains have been interred in the Necropole Zoologique of Asnières. We beg for your true sympathy.”

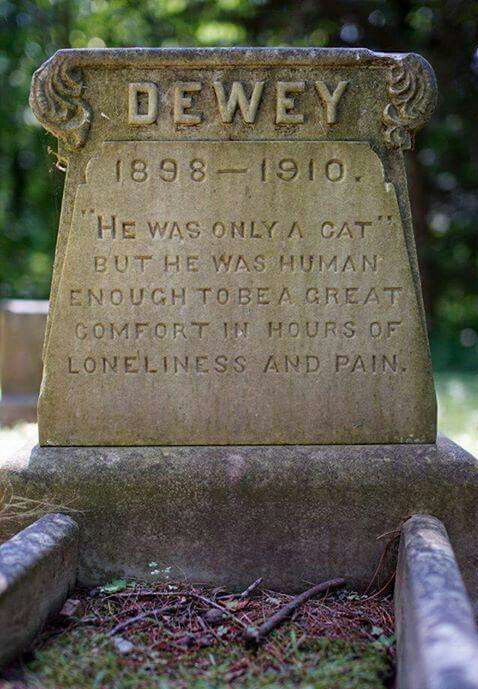

These commemorative acts were not the preserve of dogs alone. In the Ross Gazette of the 15th March, 1894, the account is presented of a London cat funeral organised by an unnamed ‘lady of distinction:’

A CAT’S FUNERAL.

In certain circles in Kensington deep interest has been taken in the funeral of a cat belonging to a lady of distinction. It may be questioned if a pussy has ever had so solemn a burial. Except that the church did not lend its sanction, the function was conducted quite as if it had been the interment of a human person of some importance. A respectable undertaker was called in and instructed to conduct the funeral in the ordinary way; the body was to be enclosed in a shell which would go inside a fine oak coffin. There were the usual trappings, including a plate on which was inscribed the statement that “Paul” had been for 17 years the beloved and faithful cat of Miss -, who now mourned his loss in suitable terms. The coffin, with a lovely wreath on it, was displayed in the undertaker’s shop , where it was an object of considerable interest and not a little amusement.

©Paul Koudounaris

A similar account in the Shepton Mallet Journal of the 24th of February, 1899 informed readers that a wealthy American woman, distraught at the demise of her beloved cat, had decreed that the animal should be interred within the grounds of the country club she attended. The owner’s status is clearly visible from the site of her New York address:

A CAT’S FUNERAL.

The funeral of a £1,000. cat, which is mourned by a wealthy mistress has taken place at the Long Island Country Club. The cat’s owner was Mrs. Peter Adams, of No.254, Madison Avenue, New York City. The body was shipped to Superintendent Tuthill , of the club, encased in a costly coffin with silver trimmings and green satin linen. With it came the request that the cat be buried in some quiet part of the club grounds. The request was complied with. The cat had been a pet of Mrs. Adams for many years, and was a pure Angora.

Perhaps rather more eccentric in nature are the reports of lavish avian entombments, commonly involving pet parrots. The below account in the Dundee Evening Telegraph of the 20th of April, 1935 relates the funeral of such a bird, charmingly depicting the other animals belonging to the family as ‘attending’ the service:

OTHER PETS AT PARROT’S “FUNERAL”

Giles, a Brazilian parrot, has been in the family of Mrs Dyer, wife of Captain A. J. Dyer, of the King’s Head Hotel, Romford, for nearly 70 years.

Now he has died.

He has been buried in the garden adjoining the Romford Bowling Green. A spray of white narcissus marks the spot.

Giles had four favourites – two dogs and two cats.

When the parrot was being placed in its grave it was noticed that all four animals had followed the funeral possession from the house and were looking on.

Woman with Parrot by Karen Arnold is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Sometimes the animals succeeded in making their escape from the deathly proceedings. This jaunty (and rather traumatic) note on the intended burial of a pet parrot with its deceased mistress in the Daily Mirror (2nd of May, 1938), recounts the bird’s escape, protected by the opposition of church officials to zoological ceremony:

Parrot “Escaped” Own Funeral, Sent Wreath

Leicester church officials would not permit the burial of a parrot with its mistress , Mrs. Mary Pollard, on Saturday, which had been her dying wish. So it escaped death – and sent a wreath of tulips.

Mr. Pollard told the “Daily Mirror” yesterday: “My wife begged me to kill forty-year-old Dexy and bury them together, but the thought of it nearly broke my heart. Now I shall continue to keep him as a pet.”

Elsewhere, the trend was often met with a sense of hostility surpassing the playfulness customarily underlying such accounts, particularly as regards the involvement of liturgical practice. A stark example of this attitude can be seen in the following piece, documenting a canine demise in Romania in the 22nd of May edition of the Hull Daily Mail in 1899:

DOG FUNERAL.

BUCHAREST, May 18.

In Bucharest a day or two since a favourite dog belonging to a man living in the Strada Acvila died, and the loss seems to have turned the man’s brain.

As a last tribute he decided to give it the “rites of the Church,” and in all seriousness and grief has the dead dog clothed in a splendid dress and then laid out on an elaborate catafalque, constructed according to the custom of the Greek Church, and surrounded with flowers and candles, and incense burning!

A squad of gendarmes, however, arrived, and entering, seized the dog, which was taken away and chucked on a rubbish heap, and the catafalque, etc., overturned and thrown into the yard.

This example, printed in the South Wales Daily News on the 12th of December, 1879, is another example of such mockery, manifesting a palpable antipathy towards the entombment of pets. Dripping with sarcasm, the writer barely attempts to conceal his criticism of the proceedings:

A DOG’S FUNERAL.

An American genius has managed to spend a good deal of money on a dead dog, who must now be worth more than a living lion. This animal has been fashionably buried in a “casket,” or coffin, as the English say in their patois – a casket with solid silver handles and plates. The interior of the casket was lined with white satin and silk trimmings. The lamented hound was carried to his long home on the casket, covered with a mantle of white satin. Six carriages full of sincere mourners followed him (or her) to a New York cemetery, where he was laid in the family vault of his master. We are not informed, but can easily believe, that his owners engraved R.I.P. on the casket, under the impression that these letters mean “Respected in the parish.” Daily News.

‘Faithful Dog’ by Natalie Maynor is licensed under CC BY 2.0

In the aftermath of the Victorian era and the changing nature of Britain’s status on the world’s stage, there arose more ‘exotic’ accounts of such ceremonies. Bound up with the problematic discourse of empire and the reductive dichotomy at play between East and West was a tenor of journalistic report relaying the details of the commemorative efforts surrounding the deaths of monkeys in India, themselves important sacred symbols of religious and cultural beliefs patronisingly dismissed in these accounts as incomprehensible quirks or uneducated practices. Such pieces were clear attempts to perpetuate the supposed cultural preeminence of the empire on which the sun never sets, written in such a way so as to titillate the reader, denigrating non-western religious acts to the realm of ‘barbarian’ stereotype. For instance, this article in the Gloucestershire Echo of the 11th of March, 1926, reports on this kind of simian passing and interment amongst a number of other smaller items on Empire and Imperialism:

FUNERAL OF MONKEYS.

Quaint Scene in Mysore.

Twenty-five wild monkeys have been poisoned by some unknown person in a village near Mysore. Orthodox Hindus venerate the monkey, and the incident is regarded as an outrage to religious beliefs. The bodies of the monkeys (says a correspondent of the “Morning Post”) were dressed in funeral garments and carried in solemn procession through the principal streets of the city to the cremation ground, where they were disposed of with Shastric ceremonial.

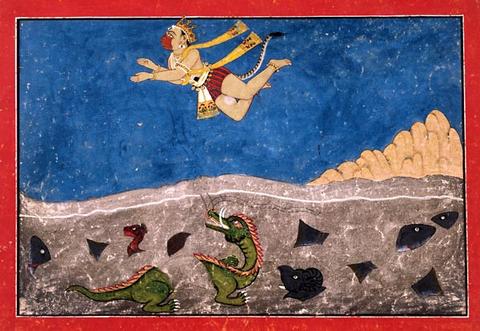

The Hindu monkey god Hanuman leaps over the ocean (© Museum Rietberg Zürich; Photo: Rainer Wolfsberger)

There are countless other examples of the practice of animal entombment preserved in the local and national newspapers of the nineteenth, twentieth and, indeed, the twenty-first centuries, testament to the widespread nature of the phenomenon and the growing need for the extension of commemorative ritual to those beings whose quiet loyalty and fidelity is so much a component of the human experience for a large number of people. Indeed, the preservation of memory in regard to deceased pets can be traced back thousands of years, a well-attested incidence in the ancient world. Not only did an archaeological dig in 2017 in Egypt uncover the remains of an animal cemetery in which dogs, cats and even monkeys were buried, but the Roman poet Statius, writing in Book 2 of his collection of occasional poetry, the Silvae (circa AD93), dedicates a poem to the eulogy of his patron Atedius Melior’s parrot (psittacus eiusdem), a bird in receipt of a sumptuous send-off:

Yet he is not sent to the shades ingloriously: his ashes steam with Assyrian spice, while his fragile feathers smell of Arabian incense, and Sicilian saffron. Unwearied by slow ageing, he mounts the perfumed pyre, a brighter Phoenix.

(2.4)

Statius’ Silvae (© Oxford University Press)

Ultimately, the emergence of such monumentalisation has the effect of exposing the problematic dichotomy between animal and man, vividly demonstrating that we cannot subject to demarcation the intrinsic need to perpetuate memory as neatly as we might think. Rather, we are enmeshed within the universality of beings that characterises existence, putting one in mind of the French author Colette’s pithy aside:

‘Our perfect companions never have fewer than four feet.’

A Grave Announcement (@AGraveAnnounce)