- Far spread below doth London wear,

- Its cloud by day, its fire by night–

- Yet scarce with heavenly presence there

- Shrined in the smoke or pallid light.

- Incessant troops from that vast throng

- Withdraw to silent colonies;

- Where houses, lo, are fair and strong,

- Though ruins, all that dwell in these.

- Yet, ‘neath the universal sky,

- Bright children here too run and sing,

- Calm verdure waxes green and high,

- And grave-side roses smell of Spring.

In Highgate Cemetery, William Allingham (1850)

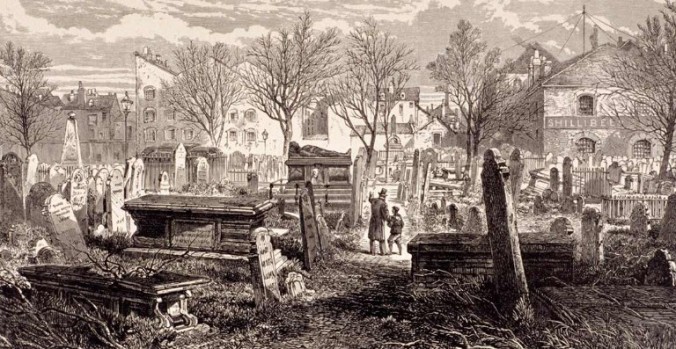

Highgate East (Image © A Grave Announcement)

Last night I dreamt I went to Highgate again: the creeping foliage of its lingering woods, the wealth of stones arrayed like a clamouring crowd, the quiet tittering of its avian population, its wildflowers dotted in a universe of stars. Seemingly labyrinthine paths meander through the arboreal canopy, a profusion of markers wind their way towards the horizon, throngs of personal stories gathered about the woods, quiet voices softly speaking both the death and victory of time. It is an affecting sort of place, the kind of site at which your heart beats with wonder at the very act of passing through. As the genealogical adage attests, we are always only passing through. In Highgate, this transience is written into our shared history, carved into the stones of those who have gone before, families occupying that very ground from the dawn of the Victorian era to the technological jungle of our own period.

In early nineteenth century London, burying the dead was a dark and grotty business. As the population of the city swelled from around 1 million to 2.3. million souls, the growing urban sprawl, in addition to the associated trend for interment within the city limits, gave birth to overflowing graveyards riddled with disease and putrefaction. These unsanitary conditions were even said to contribute to the outbreak of illness in surrounding dwellings. Worse still, decaying matter was known to leak into the water supply. There were even reports of sewer rats desecrating bodies. All was disarray. Burial grounds were ransacked, cadavers taken away to be sold illegally for medical purposes. Corpses were routinely dismembered in order to increase space for further committals. Gravediggers commonly worked in conditions so cramped that recently interred bodies were violently disturbed. These were grisly and unregulated places. Horrifying scenes of putrefaction. Those who had passed on were clearly unable to rest in peace. Something had to be done to ameliorate the atrocity of the prevailing sepulchral practices.

Cemetery at Bunhill Fields, Finsbury, London, 1866 © Natural History Museum

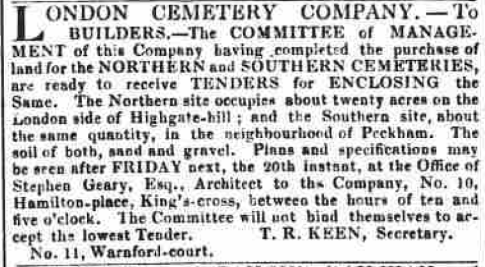

In 1832, bowing to pressure from those seeking reform, an Act of Parliament was passed urging more burials outside London, seeking to promote the establishment of private cemeteries free from parish control. The construction of Père Lachaise in 1815 with its emphasis on a landscaped ‘garden’ layout, a space defined by artfully arranged plants and imposing architectural features, had a huge influence on the changing conceptualisation of the cemetery in this period, becoming something of a model for those following suit in the British capital. In the ensuing nine years after the above decree stipulated the incorporation of a General Cemetery Company ‘for the interment of the dead in the neighbourhood of the Metropolis,’ seven such sites were selected and developed, beginning with Kensal Green in north-west London. Dying was now reborn, interment made corporate property, as this General Cemetery Company inspired a number of other such enterprises, resulting in a wealth of new burial grounds over the next decade. These site were later gathered together beneath the informal nickname ‘The Magnificent Seven.’

Part of the gatehouse at the entrance to the West Cemetery (Image © A Grave Announcement)

Highgate is a site of enormous proportions. Now divided into its western and eastern halves (see the forthcoming second part of this post), the former can only be entered via a guided tour (you can book online here). The imposing and turreted Gothic gatehouse through which one enters plays host to both an Anglican and Nonconformist chapel, whilst its arch proudly proclaims the ‘London Cemetery’ moniker of its founding company, formally established in 1836 in imitation of the aforementioned corporation at Kensal Green. The design apes that of a triumphal arch, as if heralding its own deathly boulevard, a via mortis, stygian thoroughfare penetrating the gloom. This is more apt than ever when one realises that, beneath the entryway, a tunnel was carved out to receive coffins for transportation via an hydraulic lift between the Anglican mortuary chapel and East cemetery expansion, a discreet passage for casket removal, slipping quietly beneath the carriage-laden and thronged street amidst services for the dead, a way to ensure that the body remained continuously within consecrated ground between ceremony and inhumation.

Once Upon a Midnight ‘Geary’

Stephen Geary (1797-1854) was appointed as architect for the original burial ground on the west where, in a fitting coordination, he was himself later interred. Geary had been a founder of the London Cemetery Company formed for the purpose of developing Highgate, and was thus a perfect candidate for bringing this sepulchral vision to life. To support his efforts, he employed James Bunstone Bunning as surveyor, later a City of London architect who designed who designed, inter alia, the City of London School, the City Prison and parts of Brunel’s Hungerford Suspension Bridge. In addition, David Ramsey, renowned for the beauty of his gardens, was brought on board as landscaper and nurseryman.

James Bunstone Bunning, Illustrated London News (October 28th, 1865)

Morning Advertiser (18.05.1836)

The team was now in place – next, the site. Seventeen acres of land on the slopes of Highgate Hill, originally belonging to Ashurst House and its estate, was purchased for £3500 (c. £211,500). It took three years of careful planning and execution to bring the project to completion, with a methodical approach to formal planting and configuration of the grounds, all accompanied by the grand architectural models of Geary and Bunning. Such was the ambitious scale of the undertaking that the London Cemetery Company even developed their own brickworks to ensure timely delivery.

In September 1838, an announcement was made in the Morning Post and elsewhere in the press, informing the residents of the city that ‘the Highgate Cemetery is finished and ready for Consecration.’ Once the latter had taken place, the first occupants could lay down to rest in sacred earth.

The area was consecrated on the 20th of May, 1839, by the Right Reverend Charles James Blomfield, Lord Bishop of London, who swiftly dedicated the ground to St. James.

Charles James Blomfield by Thomas Lawrence (St Edmundsbury Museums)

Blomfield was a former classical scholar known for his fierce debating skills in the House of Lords. In previous years, he had presided over a scheme to accelerate the building of churches in the capital with, according to his fellow churchmen, ‘almost superhuman exertions.’ He brought this ecclesiastical drive with him to the Highgate ceremonial, and, as a man with interests in the ancient world, must have been impressed by the sheer splendour and scale of Geary and Bunning’s architectural foundation.

The cemetery’s land was partitioned in accordance with denomination – the Church of England received fifteen acres and the Dissenters, two.

The Globe, 25.05.1839

The first burial took place six days later, on the 26th of May. Elizabeth Jackson, aged 36 and formerly of Little Windmill Street in Soho, had paid 3 guineas for the privilege of a Highgate interment. For a considerable period, however, Elizabeth’s grave stood mournfully bereft of neighbours – initial applicants to the cemetery were distributed throughout its acres, favouring lots away from the entrance and main paths proper.

The Grave of Elizabeth Jackson © Bill Nicholls

Slowly and steadily, however, from this first quiet entombment of Elizabeth, West Cemetery became grandeur itself, a site bedecked with saxeous funerary monuments, pomp-laden announcement of magnificent ceremony, ever in flux, proliferating and gasping under the weight of its own departed. It was the place to be and the place to be seen to be dead, a fashionable funereal locus where the well-heeled flocked in their droves, enviously admiring each other’s passage into the earth. Highgate was on the map.

From its very inception, the London Cemetery Company advertised widely, building momentum around the idea of a Highgate interment, an insistent presence in the city’s newspapers. This early offering from The Morning Post in May 1839 presents a simple summary of the services available, advising interested parties to apply at the corporation’s offices in Moorgate-Street, at the ‘back of the Bank.’

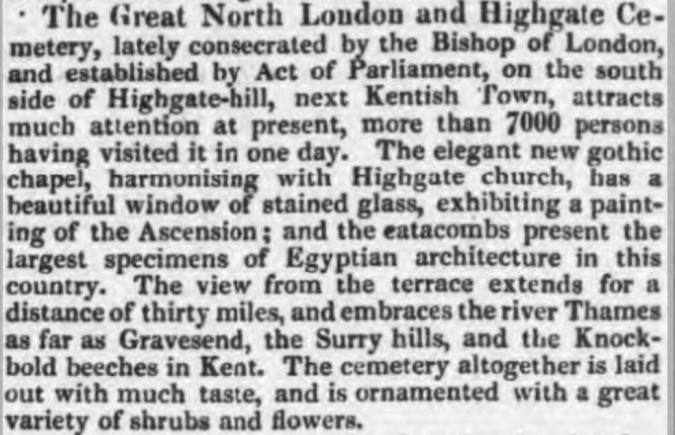

Not only was Highgate presented as the latest and greatest burial site for your consideration, but it was also configured as somewhere you ought to visit for your own edification, a place to roam, ‘OPEN DAILY till Eight o’Clock P.M., free of charge.’ Bury your relatives and, while you’re there, take advantage of the grounds. Soak up the sense of place. Be at one with your Dearly Departed. According to the Stamford Mercury of the 9th August, 1839, Highgate’s popularity was such that ‘more than 7000 persons’ had visited in one day. The piece singles out the architectural wonders of the site, in addition to ‘the view from the terrace’ which ‘extends for a distance of thirty miles, and embraces the river Thames as far as Gravesend, the Surrey hills, and the Knock-bold beeches in Kent.’

Into the Woods

Upon entering this great place and following the path up the hillside, the visitor is struck by the gateway to the impressive Egyptian Avenue, a Pharaonic arch flanked by two columns on either side. This is, in turn, guarded by twin obelisks, stone guardians of the dead. The structure is a striking example of the Egyptian Revival style so beloved by the Victorians, an architectural system grounded in the recycling and reworking of the motifs of ancient Egypt. Interest in the latter emerged from the fanfare surrounding the Napoleonic campaigns in Alexandria and Cairo (1798-1801), a military cavalcade which contained, rather unusually, a sizeable contingent of scholars and scientists. You may be familiar with Pierre-François Bouchard’s associated discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799, now housed in the British Museum. Reports of the work and finds of these intellectual expeditionists generated a growing fascination with Egyptology in Europe, a preoccupation which had a great effect on the aesthetic fabric of the continent. Indeed, the centrality of death to ancient Egyptian ritual practice was a phenomenon which could be readily transferred to the emergent funerary architecture of the nineteenth-century burial places of Western Europe.

Entrance to the Egyptian Avenue

The road beyond this entryway continues at a gentle incline. Bordering the track are lines of family vaults, home to the slumbering dead, their entrances adorned with a variety of funeral symbols. These cavities were made to accommodate multiple coffins in order to ensure that families could be buried together, sealed units, metaphorically and literally, affection and companionship assured until the end of time. Leaving this sepulchral cavern behind, one emerges into the almost indescribably exquisite Circle of Lebanon, a wheel of tombs arranged around the roots of a magnificent cedar tree, a striking mass in place long before the construction of the cemetery, part of the grounds of the aforementioned Ashurst Estate. I felt as if I had emerged into a timeless space, where nature and architecture were in happy communion, where as many memories circulated as the abundant needles of the cedar’s leaves. Interestingly, the circular disposition of these burial chambers has formed an enclosure serving as an impromptu plant pot within which the tree is contained. There are two rings of such tombs: the inner circle of twenty vaults was part of the original design and was supplemented by an outer addition of sixteen sepulchres in the 1870s, a facility expanded in response to the popular clamour for a slice of this particular piece of eternity. In addition, one finds here the columbarium, a series of cubicles fashioned for the purpose of holding urns full of ashes, an unpopular provision in the Victorian period when cremation was looked upon with righteous suspicion. It was only following the passage of the Cremation Act in 1902 that the practice became more commonplace, and the notion that the sanctity of the body remain undisturbed post-mortem began to be overcome.

Circle of Lebanon © Bill Nicholls

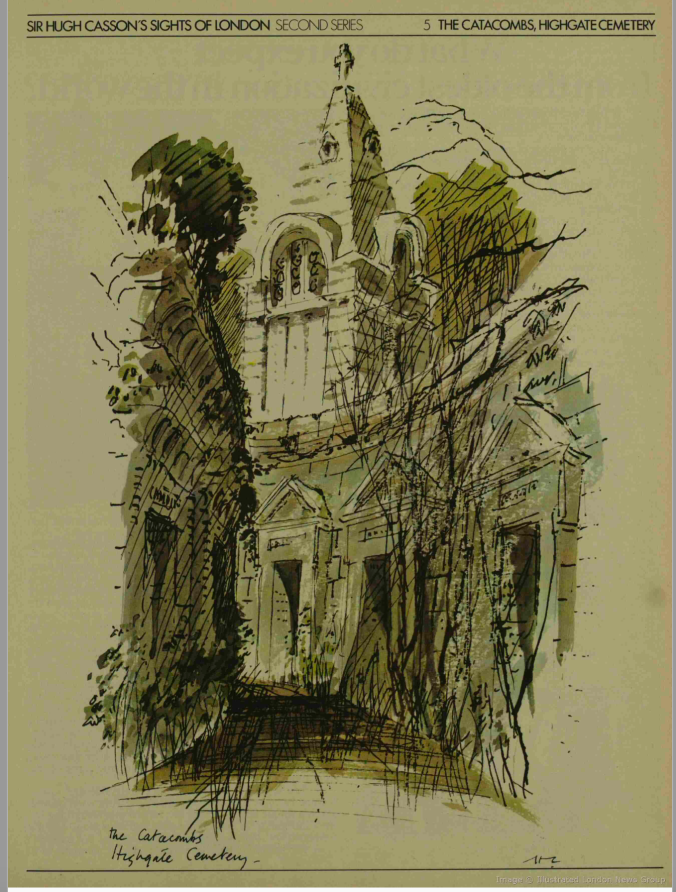

In this same area, the terrace catacombs in Gothic style are to be found, burial spaces hewn from the very hillside itself. Indeed, they occupy the same space as the previous deck of the garden of Ashurst House, formerly a splendid viewpoint from which to gaze out upon the teeming life of the city. Visitors to the cemetery would seek out this spot for a genteel promenade, ambling up and down in their finest, away from the heady stink of the London smog. As an aside, if you enjoy bitumen and random facts intended for pub quizzes, the terrace is also apparently the earliest asphalted building in the UK. Within the structure, one encounters a brick-vaulted, eighty-yard long passageway filled with separate recesses on both sides, capable of housing an entire coffin from floor to ceiling. In total, the catacombs hold eight hundred and forty such caskets in apertures which are themselves sealed with memorial plaques or small glass windows for inspection. When laying the deceased to rest in this place, coffins were apparently situated with the heads of the cadavers closest to the opening, meaning that relatives could easily commune with their dead.

Illustrated London News (01.09.1974)

Behind the Circle of Lebanon is what can only be described as an immense mass of a tomb: the eye-waveringly ornate mausoleum of Julius Beer. This is a big beast of a burial chamber, the Highgate leviathan. A square structure with bronze doors, pyramidal roof carved to resemble roof-tiles and arched windows, the edifice is said to have been inspired by the fearsome Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, and was designed by John Oldrid Scott (1841-1913), an architect experienced in the construction of religious buildings.

The Mausoleum of Julius Beer (by Steve James)

The architraved doorway bears an inscription with a powerfully simple message to passersby, identifying itself as the ‘Mausoleum of Julius Beer.’ The opulent theme continues within, as the tiled walls, golden mosaic lining the dome and Corinthian columns perfectly accompany the pièce de resistance, namely the bas-relief representing Julius’ deceased daughter Ada as a winged child, who had died of consumption aged only six, being spirited upwards to heaven by an angel.

Julius Beer is a fascinating example of the model of the self-made man. Born in Frankfurt, he came to London and promptly made an intimidatingly large amount of money on the London Stock Exchange, before gobbling up several newspapers: the Observer and the Sunday Times. A quirky and perhaps apocryphal tale accompanies this majestic tomb – having become embittered by his lack of acceptance in polite society, Julius decided that, in death, he would have the last laugh. In 1876, he parted with £800 (c. £52,950) for the site, in addition to an eye-watering £5000 (c. £330,923) for construction, placing this, the tallest and largest monument in the cemetery, in such a position so as to utterly dominate the otherwise splendid view from the terrace, thereby damning in the process a phalanx of afternoon constitutionals. We should not forget, however, that the project was, in its essence, a house of mourning for his little Ada, the adding of a bombastic note to the burial ground’s architecture of grief to memorialise his daughter. Once I myself had fully taken in its immensity, I was left with nothing but a quiet sense of humanity, thinking of the pathos inspired by the severing of the parental bond.

Relief Panel: Angel Lifting a Winged Child by Thomas

Down Memory Lane

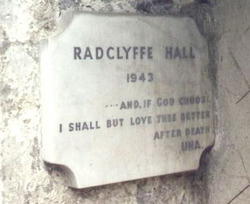

There are many other graves of note on this side of Highgate, more than a mere written piece can ever hope to encapsulate. Amidst the meandering footpaths and untamed thickets, individuals of great note have found their rest – from the poet Christina Rossetti to the scientist Michael Faraday, from the pioneering lesbian author Radclyffe Hall to the renowned novelist Stella Gibbons, author of Cold Comfort Farm. Even the eponymous founder of the Crufts dog show, Charles Cruft, can be found occupying a tomb. It is a fascinating pastiche of the great and the good, the devoted and the quiet, the industrious and the kind, the pauper and the poet. In the end, all roads lead to Highgate.

Memorial Plaque to Radclyffe Hall, Circle of Lebanon (by Scott Michaels)

Indeed, the eye is drawn not only to those graves commemorating the lives of such eternally famous figures, but also to those who, having once achieved renown, languish, known only to researchers and scholars, campaigners and active taphophiles. One example might be Ellen Wood (1814-1887), better known as the famous writer Mrs. Henry Wood, a literary figure who was as celebrated as Charles Dickens in her era. Her books were Victorian bestsellers, snapped up in an instant by her devoted followers. Particularly loved was her sensation novel East Lynne, an elaborate offering of mistaken identity and comic misunderstanding. On her death, she left an estate worth £36,000, an enormous sum equating to £2,500,000 in today’s money.

Mrs Henry Wood – Joseph Sydney Willis Hodges (© Worcester Guildhall)

These individuals of distinction rub shoulders with those otherwise unknown. As long as there were available funds, Highgate was open to everyone, with your cheque made out to death, the great leveller of us all. Take this beautiful and arresting monument, ‘The Sleeping Angel,’ in memory of Mary Nichols, wife of Bank Manager Harold. The figure atop her stony bed slumbers in perpetuity, her wings carefully folded, an expression of profound mourning. She is the perfect representation of peace.

‘The Sleeping Angel’ (Monument to Mary Nichols) by Tom Bennett

Reflecting on what we had seen, we made our way back to the entrance, steeped in poignant contemplation. My trip to the east side of the cemetery would be just as eventful, allowing me the opportunity to explore further Highgate’s 170,000 graves, and to bring yet more stories of quiet voices unheard back to life.

Image © A Grave Announcement

💀 Thanks for Reading!

A Grave Announcement (@AGraveAnnounce)

Sources

With thanks to the following which proved very useful in compiling this account:

I loved wandering around Highgate when I visited London last summer.

LikeLike